About three months before the election, my boss informed me Barack Obama was going to lose. And this wasn’t some casual assertion: my boss knew what he was talking about. He was the political director of a national political organization, and, even before the conventions, he had recognized the harbinger of Democratic defeat. “Authenticity,” he told me, “Authenticity is what the American people want, and they don’t think Obama has it: he’s too flexible, too fake.” Regretfully, I could guess the rationale. That month, Obama had reneged on two primary promises, swallowing FISA and bucking public financing. The two moves I had read as pragmatic positioning, teeing up a well-financed and centrist general, my superior considered suicidal flip-flopping, unleashing the Rovian wolves upon John Kerry 2.0. So I applauded the pragmatism; he feared the inconsistency.

He was wrong. 365 electoral votes say so.

My boss was right, though, to recognize the tension between principle and pragmatism. A caricaturized pragmatist would seem erratic, uncontrolled, but somehow justified in any decision with the cure-all, “it’s for the best.” Well, no, it often isn’t. This is why voters appreciate some principle or ideology undergirding their politicians’ views, a sense of what they’ll do and why. Thus, pragmatism often earns a costly, though unfair, connotation: hollow. But that caricature overdramatizes the tension. Pragmatism can be infused with principle, or at least substantiated by it. This (albeit uncommon) possibility came to life in the Obama campaign. They took the Chicago-style pragmatism across the country and online, building a social movement dedicated to change but able to disagree about what it meant. By creating social capital among his supporters, he could preserve his political capital, then cashing in both for a historic win.

This story starts at home.

Chicago On My Mind

Obama moved to Chicago in 1985, a little more than a year after he graduated from Columbia University in NYC. He was 24 years old and hired to lead the Developing Communities Project (DCP), a progressive coalition aiming to mobilize black churches in the area. This is when he planted his roots in Chicago’s south side, and when organizing became rooted within him.

He admits as much himself, speaking to the DCP a few years ago: “I grew up to be a man, right here, in this area. It’s as a consequence of working with this organization and this community that I found my calling. There was something more than making money and getting a fancy degree. The measure of my life would be public service.” He found not only his calling, but also his core principles. Campaigning in Iowa, Mr. Obama called it “the best education I ever had, better than anything I got at Harvard Law School,” an education that he said was “seared into my brain.” He shares his lessons from community organizing in his chapter in a 1990 book, After Alinsky: Community Organizing in Illinois:

Organizing begins with the premise that (1) the problems facing inner-city communities do not result from a lack of effective solutions, but from a lack of power to implement these solutions; (2) that the only way for communities to build long-term power is by organizing people and money around a common vision; and (3) that a viable organization can only be achieved if a broadly based indigenous leadership — and not one or two charismatic leaders — can knit together the diverse interests of their local institutions.

The power of community organizing, Obama recognized, was its associative potential, the ability to construct organic, diffuse, yet powerful machines primed to change the status quo. Politically, its strength comes from numbers: “Once such a vehicle is formed, it holds the power to make politicians, agencies and corporations more responsive to community needs.” Obama goes further in his praise, though, noting, “Equally important, it enables people to break their crippling isolation from each other, to reshape their mutual values and expectations and rediscover the possibilities of acting collaboratively — the prerequisites of any successful self-help initiative.” By empowering a community, an organizer weaves together a thick social fabric, warming individuals’ confidence in the collective and in themselves. People learn that they each are stronger together.

By empowering a community, an organizer weaves together a thick social fabric, warming individuals’ confidence in the collective and in themselves.

Within Obama’s description is a sense of political agnosticism. He presents the potential for a community to connect and tackle a problem—any problem—without obvious preference. This too comes with the territory. The organizer’s task is not persuasion, per se—he is not collecting votes or securing praise—it is problem solving. To solve problems in Chicago, Obama evidenced his methodological pragmatism, the ability both to put community views ahead of his own and to fight for solutions. “We knew what was wrong in the community but we didn’t know how to get something done about it,” recalls Yvonne Lloyd, 78, who worked with Obama. Lloyd explains that Obama insisted on “staying in the background while he empowered us,” and he encouraged residents to come up with their own priorities with the nudge: “It’s your community.” With his orders, he would do what was necessary, according to Michelle Obama: “Barack is not one of those people who fight for the sake of fighting. [He’s] willing to do it when it’s necessary,” but he knows “you have to keep the door open” to deal with the other side.

This pragmatism followed him through to 2008. He explained to Steve Kroft on 60 Minutes his method in tackling the financial crisis:

“What I don’t want to do is get bottled up in a lot of ideology and is this conservative of liberal. My interest is finding something that works, and whether’s coming from FDR or it’s coming from Ronald Reagan, if the idea is right for the times then we’re going to apply it. And things that don’t work, we’re going to get rid of.” — President Obama

Early in his career and in just a few short years, Obama had appropriated a kind of pragmatic ethos and, possibly unknowingly, a local tradition. Chicago’s South Side is a reformist hotbed, home to the University of Chicago. Its own John Dewey had championed pragmatism a century earlier, opening his very own Laboratory School just to put his ideas into action, and it’s to Dewey—not Lincoln, Rawls, or FDR—that Obama owes his ideological debt.

A Legacy of Pragmatism

Dewey connects pragmatism to principle. He adds philosophical weight to the simplified slogan, “it’s for the best.” He does this by recasting the meanings of ideas and the individuals.

As always the products of inquiry, ideas are bound up in the problematic situation that produced them. Simply put, ideas are a way of scratching an itch. And they only have value, then, if we actually use them. When faced with a problem, rational inquiry upon termination presents ideas, and Dewey claims, to make inquiry meaningful we much use those ideas to alleviate the problem. Thus, grand theories are not timeless or static; they are pliable instruments for achieving a purpose and after, should be discarded as expired. Philosophy, for Dewey, has a practical and progressive bend.

What progress, one asks? The melioration of individuality, socially, not liberally, understood. Liberals are narrow-minded, Dewey held, as they consider the individual “fixed, given ready-made.” When instead, they should know, “It is something achieved, and achieved not in isolation but with the aid and support of conditions, cultural and physical…” Social problems—poverty, healthcare, or strife—inhibit an individual’s capacity to fully engage in society and in turn stunt the development of his individuality. By recognizing man’s social nature, you can tap into the strongest force to realize his individuality and to enact change: social capital.

By recognizing man’s social nature, you can tap into the strongest force to realize his individuality and to enact change: social capital.

Dewey pioneered the term “social capital,” but the concept dates back further, most notably to Alexis de Tocqueville. The famed democratic observer detected a humanitarian impulse in American democracy. This impulse presses for liberty through associational life. Man comes together in low-level democracy—the grassroots—recognizes the commonality between himself and another, and learns to trust him, if for no other reason than he must. Or else, democracy would stall, and problems persist. This recognition underpins self-interest rightly understood, and its prevalence in 1830s America fueled a rich and productive civic life. It was social capital at work.

Dewey elaborates this concept and connects it back to pragmatism. In “Social Capital: A Conceptual History,” James Farr presents Dewey’s three key connections. First, “we leverage one part of reality against the other.” Since ideas are instrumental and men social, we should use cooperative action to solve the problems that brought the ideas into existence. Second, pragmatism gives “prominence to sympathy.” Following Tocqueville’s impulse, Dewey’s sympathy is the product of deliberation and is “cultivated imagination for what men have in common and a rebellion at whatever unnecessarily divides them.” It makes possible social life. Third, social capital can be conceived as a commodity. It can be employed or squandered just like funds or property. But it is the community’s good, so there is political justification in its investment and development.

To be fair, Dewey’s pragmatism is coarse. No grand ideas, no first principles, no five point plans, just two basic concepts. Ideas have limits, and society has power. With the recognition of both—and their underlying epistemology—comes the acceptance of a philosophical and political burden: progress. The pragmatist, free of ideological fetters, can and must leverage social capital to surmount challenges great and small.

Consciously or subconsciously, Obama inherited this philosophical tradition, and his campaign’s success testifies to its veracity.

The Social Capital Campaign

Can it get much harder to win the presidency? You’re black, your middle name is Hussein, you have little experience, and you’re up against the two most powerful political organizations in modern history: the Clintons and the Republicans. This is not an ideal candidacy; nor is it an easy one.

To grapple with seemingly insurmountable odds, Obama returned to his organizer roots. He flipped the top-down style Clintonian campaign on its head and generated enthusiasm from the bottom up. From the outset, he recognized that social capital would have to pay for his electoral victory. In his announcement speech, he said:

This campaign must be the occasion, the vehicle, of your hopes, and your dreams. It will take your time, your energy, and your advice — to push us forward when we’re doing right, and to let us know when we’re not. This campaign has to be about reclaiming the meaning of citizenship, restoring our sense of common purpose, and realizing that few obstacles can withstand the power of millions of voices calling for change.

His overtures, though noble, would not be enough alone. Remember, for Dewey, society could develop more capital through education and capitalize upon it with social movements. But Professor Obama couldn’t teach a national civics course, and a campaign for the presidency isn’t exactly a social movement. Using social capital for purely political ends seems difficult.

This, in fact, is a classic problem for political parties imitating social movements. In his study of political reform clubs in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles in the 1950s and early 1960s, James Q. Wilson recounted what one Los Angeles leader told him: The club movement is not basically a social movement…My social friends are not in the clubs. I don’t go to the homes of the people I know in the clubs and they don’t come to mine. Club meetings, Wilson argued, were “long and often dull in the extreme, with a seemingly endless agenda and interminable speakers.”

Thus, a candidate has two problems in building a social movement. First, people don’t care that much. Second, politics isn’t very social. This former is essentially a question of size: how can the candidate enlarge his campaign into something bigger than himself? The latter is one of methods: how can you bring people together in meaningful ways?

The Obama campaign had answers to both.

Change.org(anization)

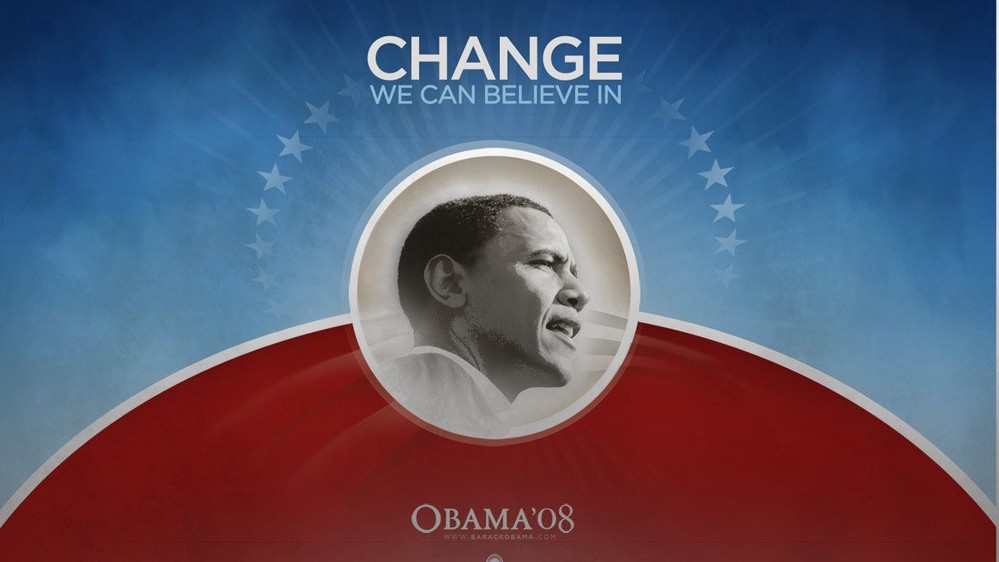

In equal parts opportunism and pragmatism, Obama enshrined “change” as this campaign theme. He promised to “bring change to Washington” and to “change the way Washington worked,” and these promises betrayed and rationalized his relative inexperience. He may be young, but he’s new and different. With Congressional and Presidential approval rating beneath 40 percent or lower, those characteristics would attract disappointed voters. Furthermore, his more polished slogan, “Change we can believe in,” surfaced in late 2007, with the less-than-subtle implication that the promises of change coming from establishment choice, Clinton, can’t be trusted. In the campaign, change could work for him.

Essentially, he crafted his campaign’s message as an agnostic creed for the American spirit.

In another way, “change we can believe in” encapsulates a kind of pragmatic philosophy. It is defined by the circumstance and promises solutions to pressing problems. Without policy elaboration, the slogan would attract interest from anyone disappointed or underserved by the status quo. This broadened his appeal, an appeal deepened by his patriotic infusion: “The genius of our founders is that they designed a system of government that can be changed. And we should take heart, because we’ve changed this country before.” Change was possible, he claimed, and everyone’s American duty to realize it. Essentially, he crafted his campaign’s message as an agnostic creed for the American spirit.

Coupled with soaring rhetoric from a diverse and likeable candidate, the message caught on. Obama himself recalled months into the race, “We started this campaign talking about change. We talked about it while we were down, and we talked about it while we were up. Now almost everybody is talking about change.” Commentators would agree that the 2008 presidential was a “Change election.” Billing himself as the best “agent of change,” Obama was able to enlarge his campaign into a broader movement. His posters read “Change” not “Obama,” his podium had “Change” plastered in front, he owned “Change.org,” and even his events were Change-themed (consider the low-dollar fundraiser, “Small Change for Big Change”). Whenever possible, Obama’s campaign would not be about him.

But a campaign is won by its moving parts, not by its design. Even with broader and deeper appeal, the movement would still need to be social. The engine of social movements is social capital, a commodity enriched and employed by meaningful cooperation. Put another way, he still needed to organize his community and put it to work.

My.BarackObama .com

As a community organizer, Obama himself would arrange and host meetings in his Chicago neighborhood. Even with a small and set demographic, mobilization and participation was difficult. Locals asked, Who is this guy? And distrust often led to inaction. Now multiply this problem a million times over and stretch it across a continent. This was the challenge facing the Obama campaign in 2007. The candidate was relatively unknown (or, even worse, misunderstood), and they needed victories in primaries and caucuses across the country. Darkening this organizational nightmare was the problem of financing. Commissioning former DNC chair Terry McCauffe, Clinton commanded the party coffers. Obama would have to reach out to and rely upon new donors to finance his insurgency.

Traditional organizing, then, was not an option, too difficult and too costly. Instead, the campaign upgraded the concept. They “crowdsourced” campaigning.

Meet MyBO.

My.BarackObama.com (or My.BO) was the campaign’s digital headquarters, open to everyone, 24/7. Upon registering, you were tasked with community building responsibilities. Your page included a scale of your involvement (1 to 10), and each “action” bumped you up. You were your own campaign manager. For finances, you could plan and host fundraisers, set personal and group targets, and watch your contribution thermometer rise. For fieldwork, you could make an online group, plan local activist events, and even download voter contact information, volunteering your cell phone as a mini-phone bank.

In a way, the Obama campaign stole its methodology from Napster. Online file-sharing platforms first popularized the notion of peer-to-peer (P2P) interaction. Instead of millions of users accessing data from one central database, the data is distributed among the users, and they connect with each other. It’s a network, not a silo. In file sharing, the advantage is speed; in politics, it’s power.

The power comes from diversity and flexibility. Each node has its own character and its own leadership, and each is able to respond to the needs in its locations. The distributed structure requires low-level activism, which in turn, creates low-level activists. As the campaign advances and gains experience, those activists become skilled, and accordingly, the campaign grows. The nature of the growth is more important: it’s personal. The campaign can infiltrate a social group with just one contact and then leverage that contact for access to the entire group. It’s viral campaigning. By getting to just one of your friends, they’ll inevitably get to you via email, phone, or invitation to your friend’s Party for Change. Since each group could be a hotbed of interactivity and participation, trust and enthusiasm developed. Thus, each person had the capacity to develop the campaign’s social capital. For the campaign, this meant more volunteers, more dedication, and more money. In turn, there was more confidence among the membership. The crowdsourced campaign was thus organic, dynamic, and expansive.

The crowdsourced campaign was thus organic, dynamic, and expansive.

The Obama campaign championed this P2P approach, employing new-media tools to craft a user-generated campaign. “One of my fundamental beliefs from my days as a community organizer is that real change comes from the bottom up,” Mr. Obama said in a statement. “And there’s no more powerful tool for grass-roots organizing than the Internet.” This was a lesson Democrats learned from the short-lived Dean campaign. The 2004 Dean campaign broke ground with its online meeting technologies and blogging, but the country just wasn’t ready yet, according to Lawrence Lessig, a Stanford law professor specializing on Internet policy advice, in_Technology Review._ Times have changed though, he continues, “The world has now caught up with the technology.” The Obama campaign recognized this early, he says: “The key networking advance in the Obama field operation was really deploying community-building tools in a smart way from the very beginning.”

And what smarter way than facebook’s? The social network connects tens of millions of people across the world, and on college campuses, serves as the community portal. The campaign decided not only to follow suit, but also to snatch the ace. Obama hired Chris Hughes, co-founder of facebook, to run online operations, and he explained his strategy, paraphrased by the New York Times:

Hughes brought a growth strategy, borrowed from Facebook’s founding principles: keep it real, and keep it local. Mr. Hughes wanted Mr. Obama’s social network to mirror the off-line world the same way that Facebook seeks to, because supporters would foster more meaningful connections by attending neighborhood meetings and calling on people who were part of their daily lives. The Internet served as the connective tissue.

The My.BO network strung together diverse and distant groups into a cohesive social network. The network, then, could capitalize upon turbocharged activist resources for meaningful impact.

That network, though, sometimes strained. “Change” housed a large coalition, and Obama had trouble serving all his masters. My.BO helped smooth tensions. When dissent did spring up, it was compartmentalized online—within one group or on one page—so the campaign could sustain its momentum while allowing disagreement. Moreover, this sense of openness and deliberation could enrich the sense of membership. Blog posts were open to comments, and the campaign sometimes responded to users’ questions. Obama himself posted a long explanation of his FISA vote to temper his angry “netroots.”

No community is without its disagreements, and as Tocqueville pointed out, the virtue of associations is that they teach us to compromise for the greater good. In this way, My.BO was a digital free association. In the end, groups would retire their complaints for the larger cause. Thus, Obama was free to make pragmatic political moves, such as that FISA vote, without sacrificing his campaign’s core. Social capital thus produced political capital.

Cashing in the Capital

The two-year campaign really came down to 12 hours: 7am to 7pm, November 4th. Get Out The Vote (GOTV) strategies are how elections are won (ask Karl Rove), since no amount of voter participation is as crucial as casting a ballot. This is where the social capital was cashed in. The campaign had been prepping activists across the country for months in basic GOTV strategies—phone banking, door-to-door, and text messaging—and this was the opportunity to let them loose.

Armed with pinpointed data from My.BO, theses self-made foot soldiers could score big in previously unattended communities. It’s difficult to know the direct impact of the ground game. Nonetheless, historic turnout (over 65 percent) and Obama victories in perennial Republican strongholds (Colorado, Omaha, and Florida to name a few) suggest the troops mattered—in a big way.

Social Capital 2.0

The Obama campaign thus enshrined pragmatism as its message and its methodology. In a way, it solved its own problems. To create a social movement, they latched onto an attractive and timely theme, and to power it, they strapped it onto an explosive online network. Its success illustrates the sustainability and power of social capital in the modern age. The Internet, at times atomizing, can knit together diffuse networks of meaningful interaction. While not a substitute, these networks can complement or even produce real-world communities, and together, they can facilitate deliberation, generate trust, and motivate action. Put another way, they can yield social capital. Then, leveraging it is the work of pragmatic organizers.

Moving forward, the lesson of the Obama campaign is at once old and new: to make one out of many, each of the many must feel like one.