These are abbreviated notes from my address to Claremont McKenna College (my alma mater) at the 2013 Forum for the Future event. Video and slides from the talk are available below.

Good morning. My name is Abhi Nemani, and I’m a CMC grad of 2010. I want to start by apologizing to Darren, who helped organize this. I was supposed to get him slides by Monday. I’d prepped a deck, was going to send it. Then I looked at all the other talks on the agenda and realized mine was entirely out of place. Last night I scrambled and tried to write something different about the liberal arts and technology because I felt like that was a theme for this set of talks and also for this weekend, so I’m going to try to connect the dots, if I can, between technology and the liberal arts, but it’s going to take me a minute, so bear with me. Okay?

This story starts in Kenya.

Last year I was fortunate enough to be brought along by the World Bank as a consultant to Kenya to help them look at open data. When you get to Kenya, you see a lot of new things — particularly if you grew up in a small, rural town in Midwestern America. You see a country dealing with corruption — the legacy of a corrupt regime — and struggling to press on.

You see baby elephants, as well, and that’s fun, but you also see this:

You see people exchanging currency with their cell phones. You get out of a cab, and you just see someone text the driver. You’re at a convenience store, and you see people texting the cashier. That surprised me. Kenya is not exactly as advanced technologically as the US. We have Square here or other modern technologies. We have our iPhones. Not as much there, so it’s like, what’s going on? I asked somebody, “What is this?” They said it’s a thing called M-Pesa, and I said, “What’s that?” They said, “It’s revolutionary,” and this is why:

In a country like Kenya, they don’t have the kind of financial security that we have here. The banking system can’t be trusted. Currency can be stolen. You can’t trust the means of currency. Well, M-Pesa changed that. M-Pesa let’s you send money from your phone to somebody else, actually initially just changing minutes as currency, and eventually they built that as it’s own form of currency, itself, where you could trade real dollars.

Initially that’s just interesting, right? You think, “Wow, they leap-frogged modern currency, right?” You don’t have to use as much paper. You don’t have to use credit cards. You can just use your phone. iPhone users would love that, and I don’t have to carry around my wallet (and even here in the U.S., I’m a huge fan of Venmo, which does basically this), but the real interesting thing was the impact on that society.

Beforehand, you were fearful of public and financial institutions, which were historically corrupt and inaccessible. And so, you keep your money, literally, close to your chest. You would keep your money under your mattress. You stay regionally within your home. You couldn’t move into the city, but M-Pesa changed that. It let you take your money out from the mattress. It created a modern economy, and here’s what’s great about it: It got people back into the cities, and created trust in civil society. Now you see vibrant urban corridors, bustling with street life and economic activity, and humming with the sounds of busses and cars shuttling residents back and forth from their rural homes and their urban jobs. Not at all unlike what you see in westernized countries, but instead of payment by plastic cards, it’s by SIM card.

I bring up the story of M-Pesa to show you an example of how profound technology can be, how big of an impact it can make on a society and on a people in a positive way, but we all know that it’s not always the case. Sometimes technology can be used for identity theft. Sometimes technology can be used for privacy violations, and most recently we all know about PRISM and its effect on our country here.

Technology can be a double-edged sword.

I tell these two stories, these two examples juxtaposed to pose a question, what ought technology do? What role do we role do we want technology playing in our society? You may not think this is an important question, but let me tell you why I think this might be one of the most fundamental questions we have to address.

Let me share a a quote from Marc Andreessen, a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley, wildly successful, early in Google, early in Facebook, and he watches technology very closely. In a recent Wall Street Journal article, he said this,

“Software is eating the world.”

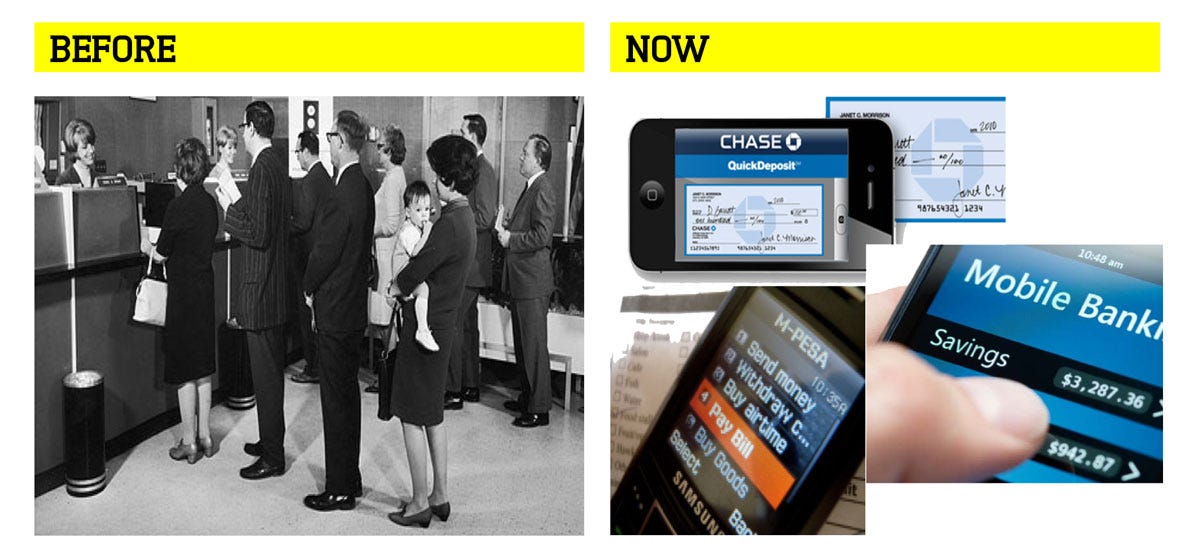

What did he mean by that? He’s looking at the way software has disrupted core industries in our society. The post office is gone, publishing is gone, media, and let’s return to financial institutions. We all probably don’t remember this but back in the day, you’d have to get to the bank before 4:00 on a Friday. If you didn’t, you wouldn’t have any cash on the weekend to go out. I can’t tell you the last time I’ve gone to a bank because this industry has been so profoundly disrupted by technology. You can take a picture of your check and deposit it in your account. You can pay people with Square using your mobile phone. The financial system in this country has been revolutionized with technology.

Software is eating the world.

Then, bringing those two themes together, I think we’re asked another question. How will technology reshape our society? Now for a lot of the folks in this room, you’re probably thinking, “Well, that’s not a question that I can grapple with. I’m not a technologist. I don’t know how to code, and you know, the apps on my phone work just fine. Whatever.” Let me tell you something. This is something we all here have to answer, and I’ll tell you in a minute why I think we’re best equipped to do that.

This is a quote from a former Google engineer. He was riffing off Ginsberg’s “Howl.” He said this. He said,

“The greatest minds of my generation are optimizing click ads.”

Fantastically talented engineers aren’t using their skills for good. They’re using it to make a profit. They’re not asking these hard questions, so who will? I think we have to, and this is the connection back to the liberal arts because even if you think you don’t have the skills for technology, because of the liberal arts, you’re equipped with the skills to analyze, to think, to read, to write, the skills you need to grapple with these important questions. More than that, I think the liberal arts also teaches us important values.

You guys know this, right? In Gov 20, we read Tocqueville and learned about how democracy works in the modern age. In Lit 10, we read Orwell and learned about the importance of good communication and the curious dynamics of power. In Philosophy 10, we learned about Rawls and our connection to people. These are our values, and the liberal arts gives us the tools to understand how they could be borne out in our real lives.

I’m arguing that we should use them to think about how technology is changing our world because in today’s age, it is technology that best enables us put them into action. That’s what’s changed. Now, when you see corruption, or inefficiency, or disenfranchisement, something as simple as a few lines of code can dramatically shift the status quo. With a few lines of code, you can take your liberal arts degree off of the shelf, and put it to work.

I want to tell you that I’ve seen this firsthand. I’m fortunate right now to work in an organization called Code for America. Has anyone heard of the organization? For those of you who haven’t, let me give you a little bit of background. I think I know a lot of the folks in the room. For those of you who knew me when I was here, I was a political nerd. I was a Rosie [the on-campus state and local government research institute]. I worked on the Port Side and Forum [the campus newspapers], but I was also a geek. I think I spotted a couple of people in the room who I personally built websites for when I was here, so I happen to be the curious mix of someone who’s passionate local government but also into technology.

So I didn’t have the most traditional college career, in class or out; thus a fair question is, what did I do with that education? Well, I was going to end up actually going to Google full time after I was graduated, but then one day on the Internet I saw this logo, and it caught my attention. I’m like, “Code for America,” what does that mean? I went to the website. It was a startup. It had just been founded a couple months prior, and it had this basic notion: “Let’s use technology to change the way government works.” It’s like, “Whoa, that’s kind of cool,” so I checked it out. It was just getting started. I had a couple months before I was going full time to Google, and I said, “Let’s see if I can hang out, maybe be helpful for a couple of months.” I sent an email to the founder, started volunteering for a couple of weeks, then a couple of months, and now it’s become a couple of years. I’m currently serving as an executive director there, trying to help understand how technology can change our governments.

So what does that really mean to code for America, and how does it have anything to do with the liberal arts? Let me give you a few examples.

Just for reference, the core thing that we do — our bread and butter — is this: a Peace Corps for geeks. Doctors have Doctors Without Borders, teachers can do Teach for America, but developers and designers, technologists, didn’t have an easy way into public service. We wanted to give them that. What we do is we pair a team of three or so developers with a city government, local government, and ask them to take on a hard problem, something like food stamps enrollment or urban blight. Take on this problem and see what’s possible, see how you can use technology to better a society.

Here’s an example of a problem they had to take on.

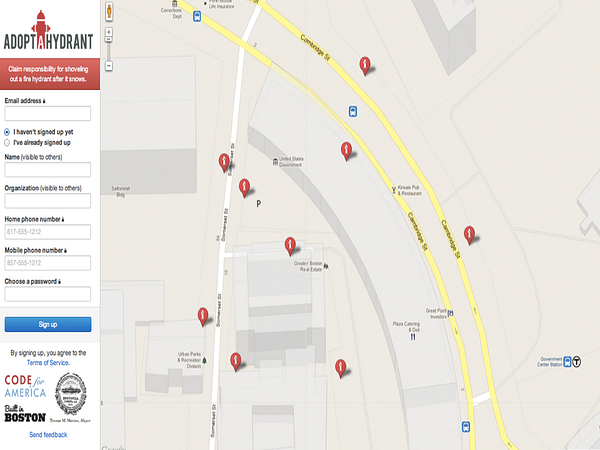

The first year we were working in the City of Boston. We send our fellows because we’re cruel, I guess, to the City in the month of February. In Boston that year there was a snowstorm, so instead of being able to do the research that they needed to do, they had to man the call center because people were calling in saying, “I can’t get to where I need to go.” While they’re there, though, they talk to some people in the call center, and they saw a fireman and asked the fireman, “What’s a problem you’re dealing with today in this crisis?” He said, “It’s this.” He said, “In snowstorms or when it snows a lot, hydrants get covered with snow, and we can’t go put out fires. We have to drive around the city and shovel them out.” They were like, “Okay, how can we use technology for that?”

Initially, the thought was, “Let’s build an app where you can just map them and track them. That’ll make it easier for the firemen to do their job,” but the fellow who was working on this was a philosophy major from Carnegie Melon, and he thought, “Well, citizens are living right in front of that hydrant. That’s someone’s house behind that. Why shouldn’t that person have the responsibility as a citizen to do something about it?” so we built this, Adopt a Hydrant. It’s a little web app, not complicated. It’s cute. You can click on a hydrant near your house. It jumps up and down. You give it a name. It texts you if you don’t take care of it, but think about this. This is self-interest rightly understood. This is Tocqueville. This is saying, “As a citizen, you should make your society better,” and technology enabled that.

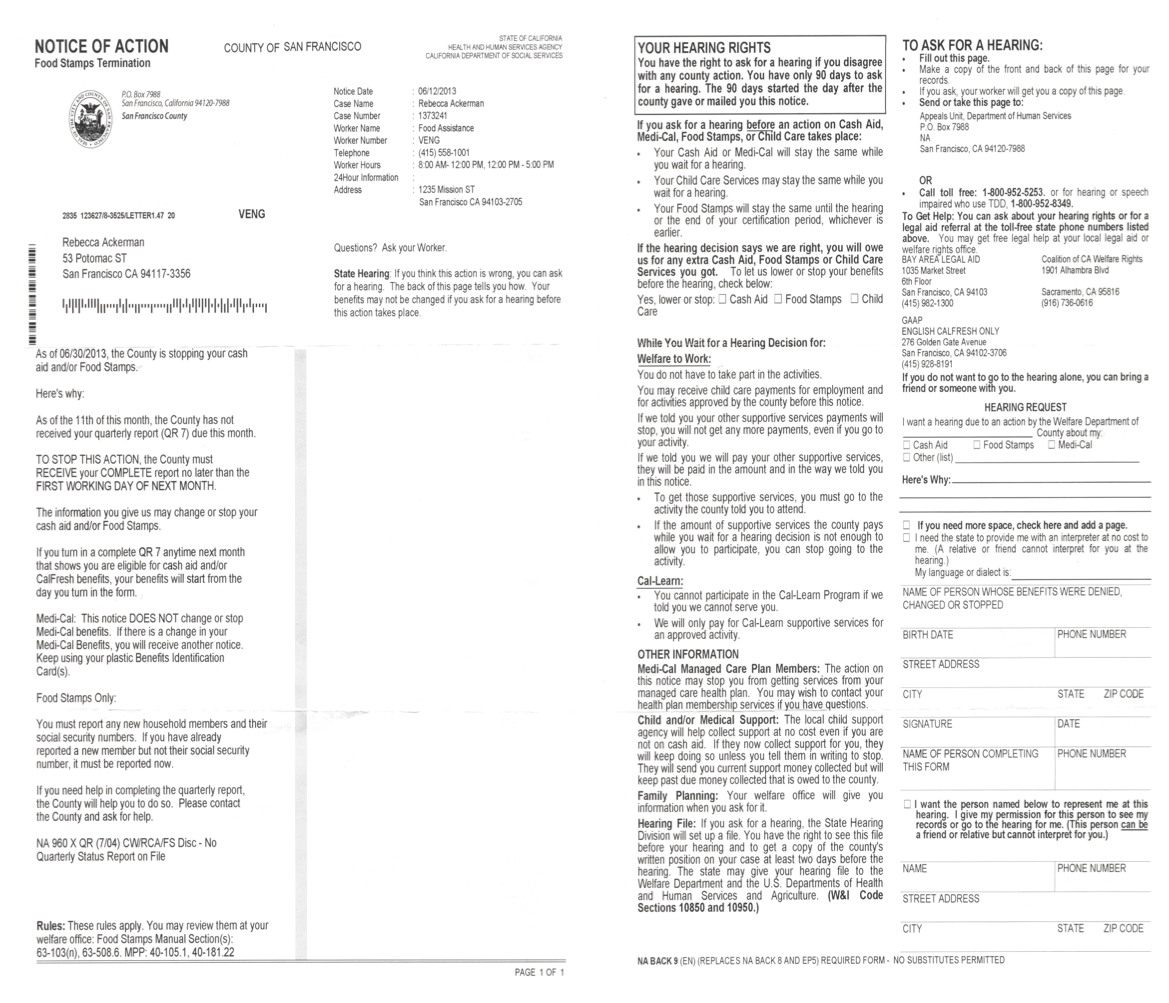

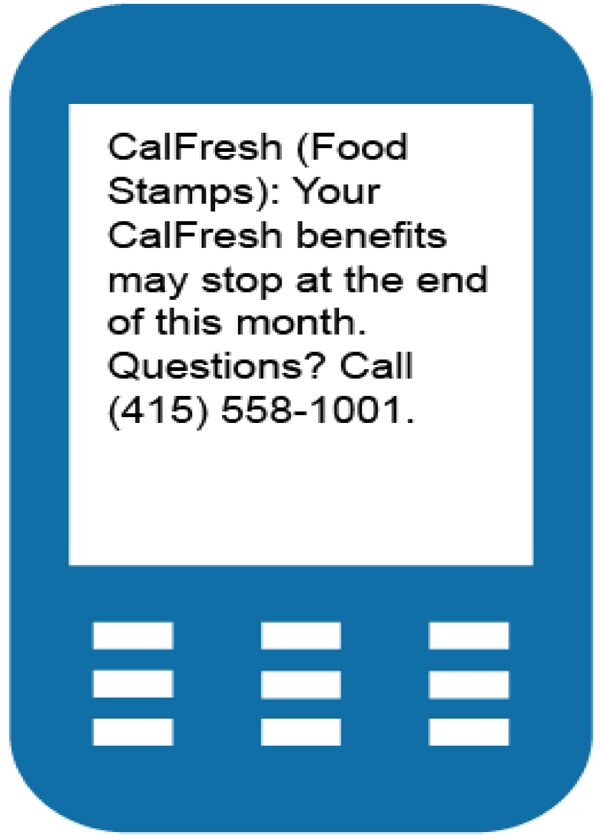

Here’s another example of a project from this year. When you have food stamps, you get credit each month at the beginning of the month, and you have to use those food stamps and report on them and what you did. If you don’t submit your report for how you use that food stamps, you get kicked off. If you ask somebody who uses food stamps, they’ll say, “Every day, the first day of the month, we go to the grocery store. That’s the day we get to go to the grocery store.” A mom with her two kids will go to the store, get the groceries, get in line, get ready to checkout, give the person the card, and sometimes they get rejected, not because they’re not eligible anymore.

It’s because they didn’t fill out this form (above), and what happens when you don’t fill out the form? They send you a letter what looks just like this, that oftentimes you can’t understand and oftentimes too hard for you to read, and so you get kicked off .That means for that month you may not have food, or at least you’ve spent three days in line in the bureaucracy trying to solve that problem.

Well, our fellows said, “That doesn’t make sense. That’s not right,” so they made a simple SMS app. I’d bet this is something that Hemingway would be proud of, short, direct, to the point. It’s showing how you can change the way you communicate in society.

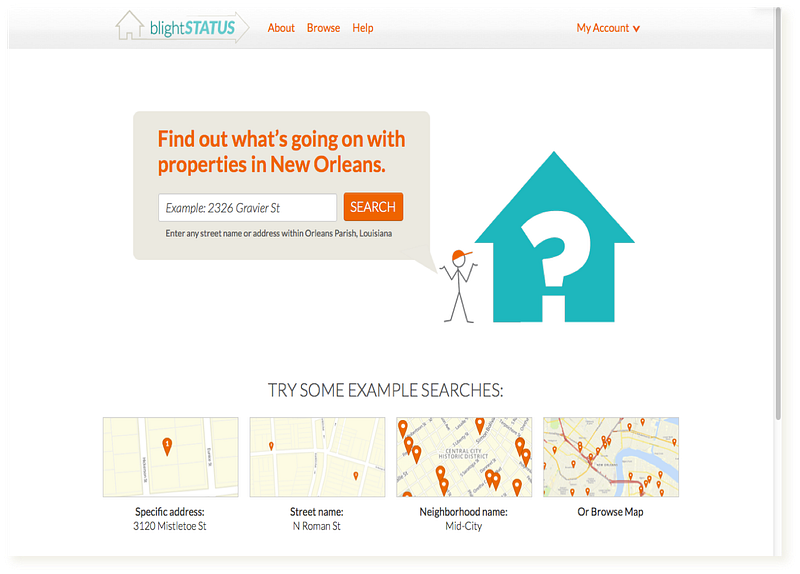

Finally, this is an example from New Orleans two years ago. New Orleans, like a of American cities, has a big problem around blight, vacant housing. Vacant housing can be hotbeds of crime, drugs, murder, and so people like this woman named Aunt Rita, get really concerned about vacant houses in their neighborhoods because they want to keep their neighborhood safe. The City wasn’t telling her the status of those vacant houses. She didn’t know what was going on, so her and her friends walked around each day for hours and mapped out the houses. Is that house safe or not? Is something being done or not? She had to do that herself because the City wasn’t doing anything. Well, we built an app for that. We built a simple app, blightSTATUS, that found all the data from the City, created a visualization, and let her see the status of it.

Again, the technology here isn’t what’s important. What’s important is this. After we launched that app, Miss Rita ran up to the fellow and gave him a hug, and along with her neighbors, she said, “You changed the conversation.” Beforehand there was a frustrated conversation. The City was on one hand saying, “I don’t know what to tell you, citizen,” and on the other hand, the citizen was saying, “City, you’re not telling us what you’re doing.” The conversation wasn’t collaborative, it was paralyzing. The application gave them a means to communicate, and it changed the conversation. When you think about a democracy and the way that we should be communicating with each other and with our government, this is how technology can be so core.

“You changed the conversation”

I’m getting over time now, so I just want to say that what I’ve learned over the last couple of years is that your values are infused in what you build. What you know, what you believe is reflected in the things that you create, and I think the liberal arts education and the values we learn through it are so critical to bring into technology because the technology we’re building now will reshape society. Thank you.