There are currently over 20 million government employees in the United States. Although rigorous surveying is lacking, anecdotal evidence suggests most are drastically under-equipped to use, leverage, or oversee technology, even though technology is becoming an essential element of policy making, policy implementation, and general administrative operations.

The high profile failures of projects such as Healthcare.gov only signal the broader issue. Estimates suggest 70% of government technology projects fail, and even that number fails to capture the opportunities for technological progress missed because of a lack of understanding — or more specifically, training.

Only recently have credentialed programs emerged to train public servants in digital technologies. These laudable initiatives tend to focus on two key constituencies with distinct purposes 1) training existing high-level executive leadership in digital vernacular and best practices; and 2) teaching incoming new employees with pre-existing technical skills how to operate in the public sector. (The latter, it should be noted, cannot guarantee that these potentially highly paid individuals will indeed choose a career in government, given the hiring constraints and payroll limitations.)

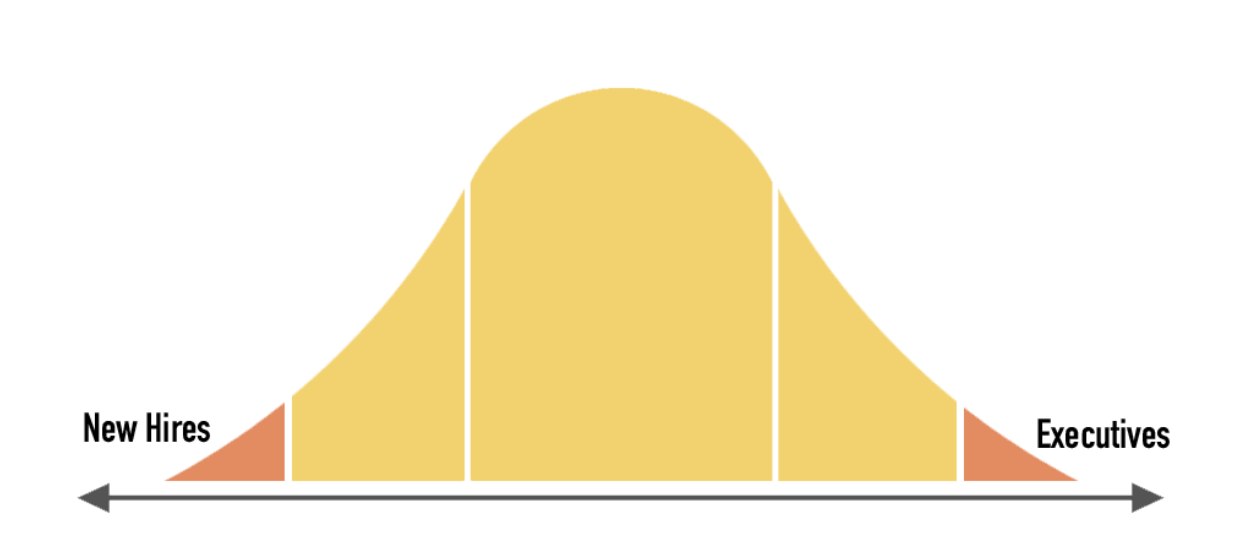

Historically, however, public policy and public administration educational programs did not include any tech component in the curriculum. This means that the bulk of government employees — the vast middle of the bell curve outside executives and new recruits — lack the technological proficiency and more pressingly, lack credible venues to level up. It seems overly optimistic to presume that these non-technical employees would or should engage in the numerous “coding camps” to become technical experts. They need not become engineers, just sufficiently proficient in technology to get the job done in the digital age. Indeed these individuals play a critical role in government operations, in every branch. If effectively trained, the outcomes would be significant. To name a few:

- Better purchasing decisions and management of contractors that would improve project delivery timelines and reduce budgetary impact

- Deeper understanding of technological needs for policy that would inform legislation

- Awareness of existing tools and solutions that would speed up and improve service delivery

- Competency using commonplace digital / data analysis tools that would inform legislative, executive and judicial decision-making

With millions of employees spread across thousands of agencies and institutions and various levels of government, tackling the challenge of digital proficiency would be a significant undertaking. Crucially, doing so without relevant and accurate data on the state of the sector would be a fool’s errand. (Indeed many organizations and companies have attempted to build technical training programs — many of which I have personally had a role in, with very limited success.) What’s needed is deeper research into the a) existing skills gap; b) effective mechanisms to address it; and c) tactics to motivate individuals to participate. Put more directly, research ought to center on the following questions:

- What skills/knowledge should analysts/advisors/aides/managers inside government have to effectively operate in the digital age?

- What skills/knowledge do they currently have?

- What types of trainings/programs would they be willing and able to participate in?

- How would such programs be financed (eg grant funding, agency allocations,, etc)?

- How would you motivate employees to participate (eg credentialing, inducements, etc)?

- How would you measure and assess the impact of these trainings (eg cost savings, project completion rates, resident satisfaction, etc)?

Fortunately, there are examples and research to pull from: federal teams such as 18F and local governments such as the City and County of Denver (Peak Academy) have run effective and well received trainings; and universities such as Harvard and nonprofits such as the OpenGov Foundation have performed research into these questions.

The goal of this project would be to pull together those valuable resources, along with new independent analysis via surveys, interviews, and focus groups into a series of tests to see what works: workshops, online platforms, or offsite retreats — or something else entirely. The scale of this challenge can only be met with rigor and creativity. That said, given the tremendous work happening to train leadership and the next generation of civic leaders, this seems to be the missing piece in institutionalizing a technologically competent and capable government: one that is more efficient, effective, and — critically — responsive to its constituents.

Appendix 1: Example Outcomes

Through various conversations with public sector experts, several (rough) concepts have emerged:

- “Quantico for GovTech”: Law enforcement agencies have highly regarded training institutions ranging from local police academies to federal institutions. Participating in these is both an honor and a requirement. By creating centralized hubs of best practices, they ensure that all employees work with a baseline of expertise. A similar model — however different at scale and expectations — could be developed for technical proficiency (ie IT managers, analysts, etc).

- “Khan Academy for GovTech”: Online learning management systems (LMS) have opened up access to curriculum ranging from specialized topics to general education, including programs from institutions such as Harvard and Stanford Universities. One could leverage those platforms themselves or their examples to build new courses for the public sector.

- Workshops or retreats: In-person short-term workshops can engage individuals who have limited time, and programs such as “RailsBridge” illustrate that a common curriculum can be taught in a decentralized manner nationally by volunteers or ad hoc employees. Provided a curriculum, existing groups (NGOs, colleges, etc) could train public servants at scale.

Appendix 2: What I’ve seen so far

- Code for America: Developed training for fellows going to work inside government, existing government officials, and civic-minded volunteers, reaching overall at least 300 agencies

- Cities of Los Angeles and Sacramento: Ran various trainings for city staff and built and deployed new technologies for use by operational staff (eg Mayor’s Dashboard).

- Dozens of GovTech startups (through EthosLabs): Tackled firsthand the challenge of ensuring adoption by government employees of new tools.

- University of Chicago: Built and taught civic tech courses for the CS & Public Policy schools.