About a year ago I was doing introductions in this segment at the Code for America Summit around some of the harder problems for government technology. I was introducing a number of speakers, most of them were civic startup founders. I found myself commenting that the first speaker was working in government… and then the next speaker actually had been a police officer. Then finally the third one too was a retired cop.

I joked, “So to build a successful civic startup do you have to have either had a badge or a gun?”

Now, about a year later, I’m thinking: maybe.

Maybe there was a kernel of truth in that quick quip.

I joked, “So to build a successful civic startup do you have to have either had a badge or a gun?”

I’ve been fortunate to be pretty close to a number of civic startups throughout the years. When I say a civic startup I mean a startup that focusing on selling to the government, on providing it tools to help them do their jobs better. In fact, I helped build and run the Code for America Accelerator, which jumpstarts civic startups. Over the course of 3 years, I’ve read over nearly a thousand applications from across the country and some from even around the world. Some were very much on point—e.g. some of the winners, MindMixer, SmartProcure, etc — and some not so much: one had more to do with peanut butter than any civic technology company ever should.

Each year, we selected each year a handful or so of some of the best startups that we could find. That’s not just in terms of their market traction, business potential, but also for the meatiness of the challenges they wanted to take on. (Why so small? We had a few punches to pick. We wanted them to be good ones. We wanted them to hit their mark.)

Since then I have studied the civic startup space closely, striving to understand whether this was a flash in the pan or something bigger. Now, more than ever, I’m convinced it’s the latter. Not only are there countless startups actively scaling, but there are dozens of new programs, ranging from eRepublic Labs or FastFWD, designed with intents similar to CfA: how can we fuel this emergent ecosystem. These sum to say —if I can borrow a phrase from Dan O’Neil — that we’re seeing the beginnings of a real industry.

Diving in a bit deeper, though, I’ve noticed a curious but consistent thread running through many successful companies: many civic startups have a cofounder or senior leader who worked inside government. Out of the 12 civic startups in CfA the first two years, 75 percent had a public sector co-founder.

These co-founders were public entrepreneurs even before they became private ones. Their businesses are as much a reflection of their insights and understanding of the government process as it is general startup and business acumen.

These co-founder were public entrepreneurs even before they became private ones.

Thinking about that I was reminded of a conversation I had years ago with one of the partners at Y Combinator, YC, as it goes by, is one of the world’s most famous, most successful accelerators. Their wins include Dropbox and Airbnb and many others like it. One YC-backed co-founder once told me that the most valuable resource he got out of the program was the founder @ YC listserv, where he could post the questions that kept him up at night, and promptly receive helpful input from other founders, new and old.

That is to say, that one of YC’s outcomes may have truly been the creation of a community, a collaborative community.

In the Summer of 2012, we were in the midst of building the inaugural CfA Accelerator, and naturally we wanted to learn from the best, so we headed down to Mountain View to meet with a YC partner. What I learned was what that YC had no specific operating thesis (unlike say Union Square that invests in networks, or Collaborative Fund and the sharing economy companies), aside from high growth potential. YC is general. They look for an interesting idea, a promising market, and most importantly, a powerful team. A powerful team, to them, had both technical and business chops, but just as important, they had empathy (my word, not his). That is to say, what they look for in a company is a team that’s solving a problem they’ve confronted in their own lives.

Famously you can look at Airbnb, where the founders needing to find a cheaper, quicker, easier, faster way to book a place to stay when they’re on the road. Or Warby Parker (although not YC): The lore goes that the founders lost a pair of glasses on a flight and then was shocked by the cost of new glasses. They decided this was a problem they wanted to solve and they built a massive and growing business (of, I’ll add, beautiful glasses) around that idea.

It’s hard to build software for somebody else. It’s hard to solve a problem if it’s not a problem that you’ve seen yourself.

Entrepreneurs solve problems they see in their own lives. That was the takeaway. In a certain way that speaks to a notion that’s very popular in the technology development space called empathy.

It’s hard to build software for somebody else.

It’s hard to solve a problem if it’s not a problem that you’ve seen yourself.

Even if it’s not a problem that you’re facing in your day to day lives you need to empathize with your customers so that way you can build software that they would find valuable.

You are to put yourself in their shoes and design for and with them.

Of course through that conversation this YC partner made a good point about their typical participant: recent top-notch engineers (say Stanford grads) whose biggest problems are things like booking a place to stay or finding cool hipster sunglasses. Government isn’t something they really deal with — particularly not out in the supportive, lush surroundings off of the 210. If anything it’s paying a parking ticket in Palo Alto or some incorporation or financing paperwork to go, but even that they can tend to rely on a vast network of legal and policy partners to handled. Government and in particular government problems just weren’t top of mind.

The question he posed back to us in that conversation is, “How do you go about building empathy for entrepreneurs for your problems?” That meant, leading them to the well of challenges ranging from access to food stamps or prison overcrowding. These aren’t exactly situations that the typical ramen eating entrepreneur takes on. (Well, maybe the food stamps.) And if visibility is the first step towards empathy, then the typical YC thoroughbred may well as be blind to these blights, he added.

But for us that was something more of a solvable problem. Code for America made its name around an intensive in-city experience. CfA sends its fellows within the city hall to see what’s working, what’s not, to understand real problems, and then build software that solve their problems. The fellows are challenged to empathize in entirely new environments. Last year one of the teams in San Mateo was trying to build tools to increase food stamp enrollment. In what is typically known as one of the wealthiest counties in the country, there are a disproportionately high number of individuals eligible for food stamps, yet notable low adoption rates. Why and how do we change that, were the questions poised to the fellows. To answer it, the decided to walk in the shoes of the people they were hoping to build for and with: they took the “food stamp challenge,” living a week only off of what they could purchase on food stampts — nothing more. (A dramatic break particularly for folks like the fellows coming from very successful backgrounds ranging from Apple, Microsoft and Google.) Another working on criminal justice reform did a night in a jail and then a ride along with a police officer. This year one of the teams in code enforcement did a code enforcement follow along with an officer and had ended up with some fairly colorful experiences including what looks like one of the meanest dogs I’ve seen out there.

Empathy was front and center to the fellowship process. The validation of this approach came later in 2012, then three of the eight fellowship teams decided to turn their year-long projects into full-blown startups. They had simply seen too much interest in their tools from across the country to not take the leap.

Each of these tools took (and many others like them), say, open data, or a citizen engagement process and built a new interface into city hall. BlightStatus (now CivicInsight) for instance took data from the vacant housing restoration / demolition process and built a simple and beautiful web app so citizens were no longer in the dark around what’s happening to that abandoned building next door. Turns out, though, that city officials and social advocates — ranging from the mayor to the local habitat for humanity—found this tool compelling. (Habitat is now their power user.) The unexpected upshot was that this consumer tool because an enterprise asset.

Since then I’ve been thinking about that a lot. How do we think not just about citizens, but also those public servants (inside cities or not) decidated to serving them? We desperately need empathy for citizens, particularly those hit hardest by the short-comings of our social safety net and the justice system. But there’s another, less discussed empathy, but no less salient. It’s the empathy behind the counter, a constant reminder that government is not just for the people, but also of and by the people.

Put another way, the users of government software are not just end citizens, but also government officials themselves. And all deserve beautiful technology that works.

It’s the empathy behind the counter, a constant reminder that government is not just for the people, but also of and by the people.

For us as citizens we live on the front side of the counter. When we’re at the DMV we see the slow processes and long ways. We sit there frustrated, all the while marveling at the speed with which we can email a colleague, play Angry Birds, and check facebook — all at the same time.

That’s the front side of the counter. That’s the citizen experience. I think the kind of empathy that we need to think more about is empathy on the other side of the counter. The kind of empathy for the government official, who’s there working with hundreds if not thousands of people coming with a “request” ranging from new driver’s license to a clearly impossible permit for parking even through street cleaning. These passionate civil servants must go through each and everyone with equal care, because that’s what governments do: they help everyone — no matter their needs.

But we don’t see onto the other side of the counter…

We simply don’t go back there.

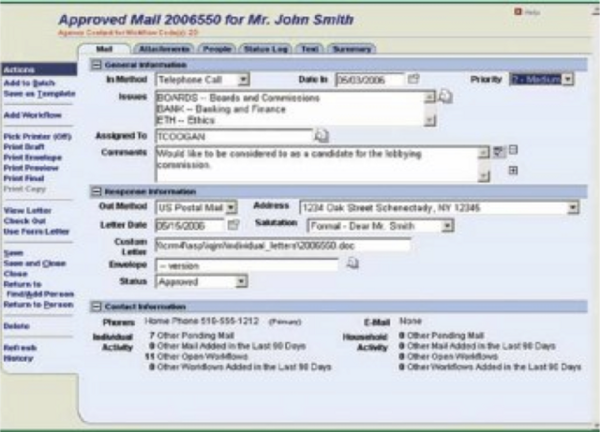

We don’t see the piles of papers stacked up on their desks. We don’t see the software probably built decades ago that they’re forced to work with.

But we don’t see what these people do. We don’t see how service line government works, how they handle this deluge of inbound. We simply don’t go back there. We don’t see the piles of papers stacked up on their desks. We don’t see the software probably built decades ago that they’re forced to work with. Worse still, we do not give them the benefit of the doubt that it’s the system, not the people within it, that’s cause those frustrating delays and headaches (Certainly, we owe them that.)

The combination of those things—not seeing the situation, and not feeling for the people within it—that’s the opposite of empathy. That’s indifference at best, disregard at worst. That’s what needs to change. We need to start building empathy when we’re thinking about civic tools. That’s not just for and with users, citizens, but for and with public servants.

We need to start building empathy when we’re thinking about civic tools. That’s not just for and with user, citizens, but for and with public servants.

Hence the correlation between a successful civic startup and its having a former government official on its founding team. They’ve seen it. They’ve been there. These are entrepreneurs who as citizens lived on the front side of the counter but as public service lived on the back. They’ve seen both sides of how technology can dramatically change our private lives and how misuse or outdated technology can frustrate the public process.

I would argue that the schism between our private technologies and our public systems is caused by this empathy gap. We need to marry the best thinking and modern approaches from the web with the specialized insight and expertise from public service. Its this mixture that breeds vibrant, organic civic enterprises.

I would argue that the schism between our private technologies and our public systems is caused by this empathy gap.

Here’s the good thing. Things are changing, and things are changing for the better in part because some of these entrepreneurs are bringing to bear their bureaucratic experience. Bureaucracy here should actually be a good word, not a bad one. It’s the knowledge of how the machine you’re striving to change, actually works. More and more programs are emerging to pair public entrepreneurs with private ones: Entrepreneurs-in-Residence in SF, FuseCorps, and of course CfA — just to name of few. These programs are yielding startups we as citizens can be proud up.

For instance, take OpenCounter. This is a fellowship application of the Santa Cruz in 2012 designed to help small business permitting that turned into a Knight Foundation-backed civic startup. OpenCounter makes it easy to go through the bulk of the business permitting process online for new entrepreneurs.

Take as an example of a classic approach where a consumer oriented or consumer centric tool might overlook the nuances and complexities of city hall. You could think, “Let’s build a turbo tax for business licensing. Find all of the paperwork the citizens have to go through. Build a streamline desktop or mobile app and then just ship that off to the city department and hope that they’ll use that data well.”

That strategy, however, misses the point entirely. All that strategy does is add another sheet of paper to the stack that the government official all ready has to deal with. All that strategy does is reaffirms this notion that change can happen entirely on the outside. All that strategy does is make an all ready complex and difficult system more complex and more difficult. Unless we start to understand and optimize the backend system, the back of the office systems that drive our governments that all we’re doing is making the problem worse.

We ought to do better than that. That’s where I think Open Counter is such a great example. One of the founders is a past CfA fellow and the other actually ran economic development for a city. These are 2 individuals who closely and deeply understood how the business permitting process works. It worked in ways like you’d expect any disaggregated system would. (They once showed me stacks and stacks of papers entrepreneurs typically have to wade through to get their business off of the ground.) Some forms go to one department, others go to another; the rules are A, in one place and B in another. Of course, none of the departments of them are open past 5pm.

As an entrepreneur going through this process you’re stuck bouncing around city hall during your work day hoping to string together an sensible, successful application, all the while frustration is bubbling up along with a few second regrets around taking this old leap into entrepreneurship.

Indeed it is out responsibility to minimize that complexity and guard against doubts around new businesses, particularly when cities of all sizes are looking to grow their economic base.

But starting there would be a fool’s errand. What the OpenCounter team did was say, “Let’s start by just understanding the process no matter its complications and then let’s do what technology does well. Let’s use technology to abstract away those complications for the citizens.”

Reengineering systems takes time, requires politics, and deep localized understanding. The OpenCounter team presciently took to heart that bureaucracy was built for a reason, often good reasons, and any (or all) complications come from years and years of policies and regulations piling on and on to where there were so many layers of bureaucracy that for government officials, answering simple questions like zoning and fees are far less easy than they seem. (I spent three years trying to compile a national database of economic development programs; I speak from experience, it’s a nightmare.)

OpenCounter’s process mapped the submissions and applications coming in from new business owners routing them effectively to the correct agency. They worked as a kind of router for a citizen into the various departments that they would need to work with. Not requiring that the citizens themselves interact with those departments over and over again, but realizing that the information and applications that they were pulling together would need to get to those existing organizations in time and in a way that they could use. Instead of adding a piece of paper to that growing pile on their desks they used email, meaning that they might even be able to take a piece of paper off.

Instead of adding a piece of paper to that growing pile on their desks they used email, meaning that they might even be able to take a piece of paper off.

Thus, OpenCounter effectively said to government agency, “While I realize this process isn’t ideal, I’m not asking you to change it overnight; instead, let’s simplify the front end for your users, and let’s work together to make sure their submissions don’t undermine or disrupt your existing processes.” That is indeed empathy.

What happens through this kind of process, you deploy a interface citizens really want to use — without hampering the government agencies—and in so doing develop a backdoor view into the bottlenecks in the existing process. Where did users drop off in the process? Which agencies struggled to respond? Which still required an onsite visit? These are the questions that an app built atop an existing governmental process offer insight into.

Software can enable data-driven reform, and empathy can make it palatable.

While this a long game, a slow game, and probably a hard one, it is one that empathizes deeply both ahead and behind the counter, both with citizens and the governments dedicated to serving them.

Software can enable data-driven reform, and empathy can make it palatable.

Empathy has emerged profoundly in the technology literature over the past few years. There’s probably many reasons for that, the growth of UX and UI practices, the number of technologies themselves and the value of design just to name a few. I would argue the central reason for empathy becoming so critical in software is that as more and more of the obvious tools are built —the tools to book hotels or collaborate with colleagues what have you— there’s a need to move away from the obvious consumer problems towards the societal or systemic problems that many have never seen before.

The same goes for any other industry, health care, education, etc: these are foreign territories for many entrepreneurs. These are new lands to chart. A commitment to empathy and all that it entails is unavoidable and indeed preferable: talking to users, working with them, building for them and then iterating over time. With a commitment to empathy, we can start to take on challenges that may not be problems of our own but are certainly problems that other people have. Now more than ever, those with the skills to build great software need empathy for those with the important problems that technology can begin to address.

That’s what will make the technology they create more meaningful. In the government context in particular, such a commitment would reframe the role of technology from the help desk to the digital service center, one positioned as an empathetic partner in the business of government. The goals of technology would be less bug fixes or even shiny new websites; instead, they would be the customer experience, citizen engagement, and optimal service delivery. Those are goals we have for great civic software.

Indeed, those are goals we have for great company.

Indeed I think too those are goals that we have for our public institutions.