These are my (slightly edited) notes from my keynote presentation at the GovDelivery Federal Communications Summit 2014 that aims to trace the evolution of the web and apply its lessons to government — the move from Gov 1.0 to Gov 2.0, from passive democracy to an active one, in the digital age.

Today, I’d like to talk to you all about advertising. Actually just one piece of advertising:

I wanted to share that with you because I thought that ad is fascinating. It’s touching and moving and funny too, but I think it’s fascinating in that it’s an ad for Google Chrome, but you don’t hear the word “Chrome” at all in the ad. You don’t hear them pitching about how fast it is, how it’s open source, how it’s secure. You don’t at any time hear anything about the browser itself. All you see are things that you can do with the browser. And you see one closing line of text:

“The web is what you make of it.”

That resonated.

It resonated because this idea of being able to talk about something, being able to present something, to pitch something without actually talking about the thing itself, just what you can do with the thing, I think is really compelling.

That’s what I wanted to talk to you today, was try to understand why that is, why could Google run ads like this during the Superbowl. They spent millions of dollars promoting these kinds of ads. How could they do that? Why would they do that? That’s what I want to try to impact together today, is what is it about the web that lets you run an advertisement like this? What is it about the web that lets you pitch a browser by just talking about what you can do with it? To do that I’ve got to tell you a little bit of history about the web. If you’ll pardon me, I’ll give you a brief history about how things have gone. You all have lived this. I have; I grew up on the web.

I’m going to walk you through a little bit of history.

A (brief) history of the web

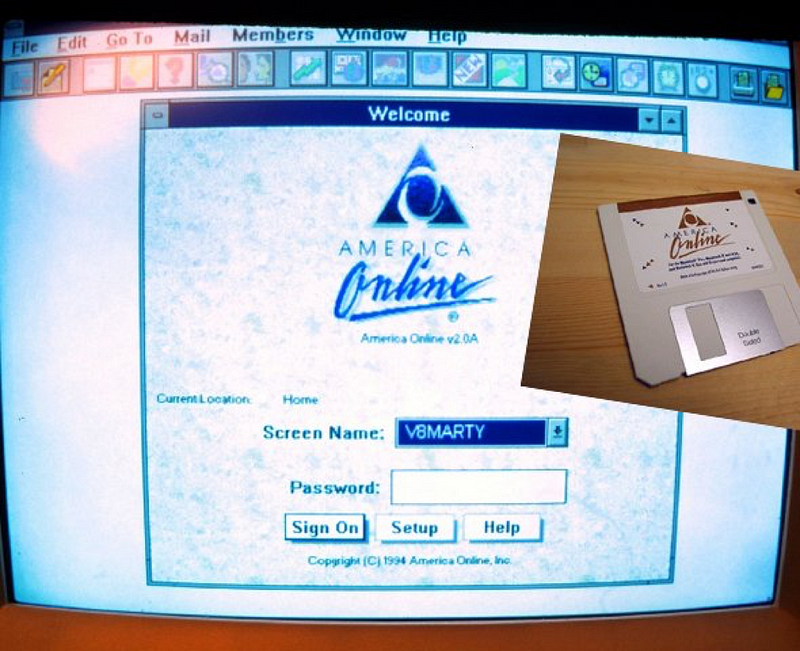

You all probably remember this. Remember this?

Actually, I’m young enough where, for me, it wasn’t the floppy disks, it was the CD-ROM drives that you get at Walmart. Remember those? They were free. (I used to use them as frisbees.) That was the initial web that we all experienced: the dial tones.

Then there was Yahoo, which was like this:

If you remember — and this is important — it was just a set of links. It was curated by people at Yahoo. They would find different links throughout the web, put them into directories manually, and let you search them that way, which was a great experience at the time, but now we know a very different one, which we’ll get to in a second. Then this, this is my favorite. This is Britannica.com:

Actually, this hasn’t changed much since 1994. If you go to the current site, it’s not too much different. Again, this was the resource for information on the internet. You would search basically a digitized version of the Britannica encyclopedia. That’s all you would have access to is that print document, now online.

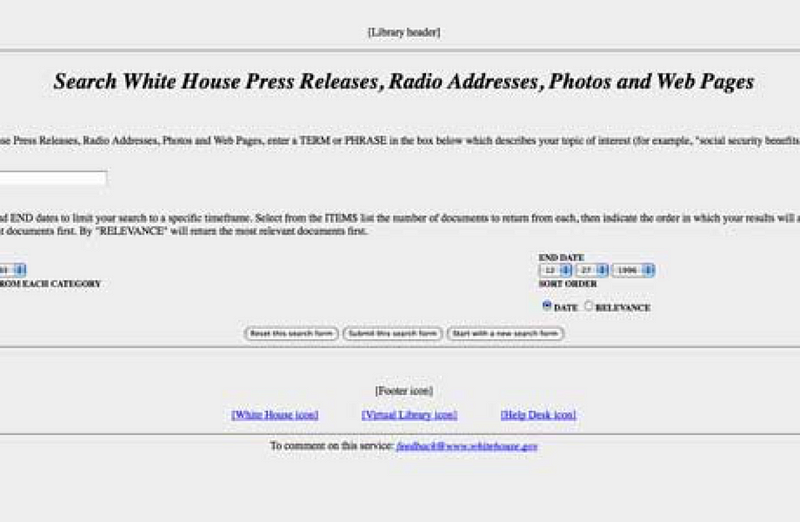

This is the White House website from 1995:

(Yeah… not sure exactly to say about that.)

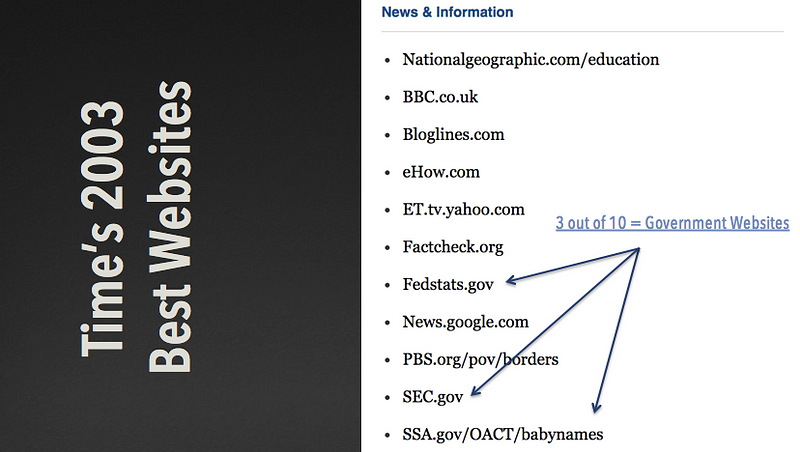

What’s shocking about that era is that government websites like this were considered state-of-the-art. In fact, in even in 2003 according to Time, 3 of the best websites were government websites.

Look at it again today, you’re not going to see that.

Why? Not just because other sites began to start using prettier typography or CSS; because things changed.

Things changed.

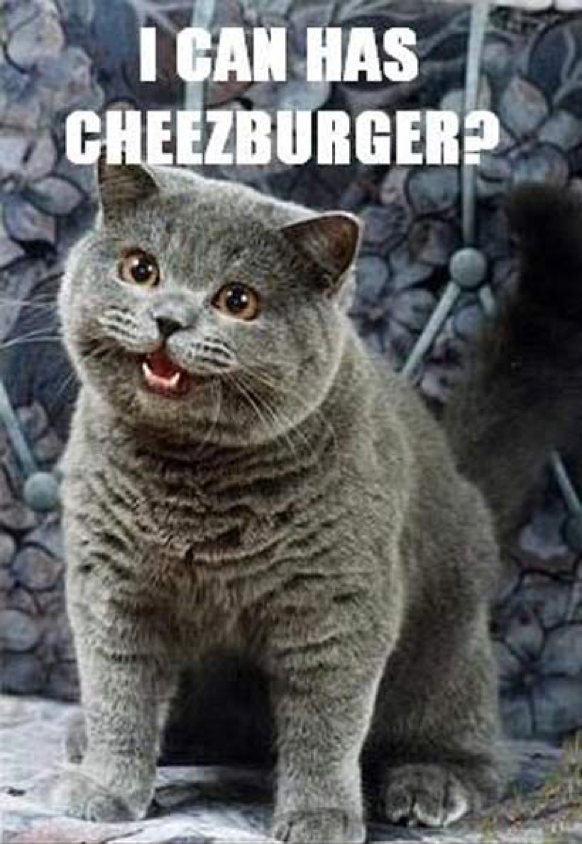

Around 2003, 2004, 2005, things changed on the web in a really profound and important way, typified I think by this:

You think I’m kidding, but I’m actually not. This, I think, was one of the biggest changes to the web is that Ben Huh and the ICanHasCheezburger team started making their own images like this, but importantly, you could make them yourselves. Think about that shift. Before hand, it was just the publishers themselves pushing you content. Now, you’re in a world where you can create content, they can create content, your friends can create content, and you all can share that together. The explosion of this site, for better or worse, is an example of how the web changed dramatically. It went from a push only experience to a push-pull, to a read-write experience. That was just the start.

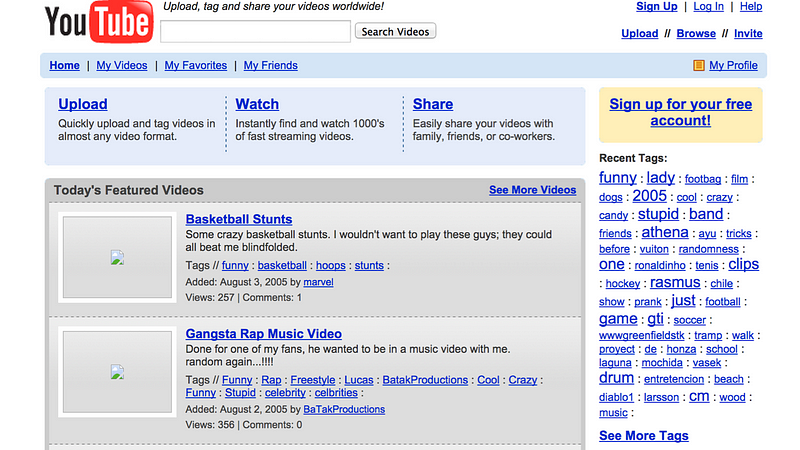

Then, you saw YouTube:

The design is much better today, thankfully. Then Facebook, of course. This is the canonical example of the social network, of how people started to connect with each other online. Then, Wikipedia. Again, think about the contrast between Wikipedia — totally crowdsourced, totally user generated, accessible for anybody in any language — to Encyclopedia Britannica, driven by one publisher, one group, one institution only. This shows you the profound change I think in the web, that you went from one encyclopedia being the resource, to all of us working together to create public information.

Consider this:

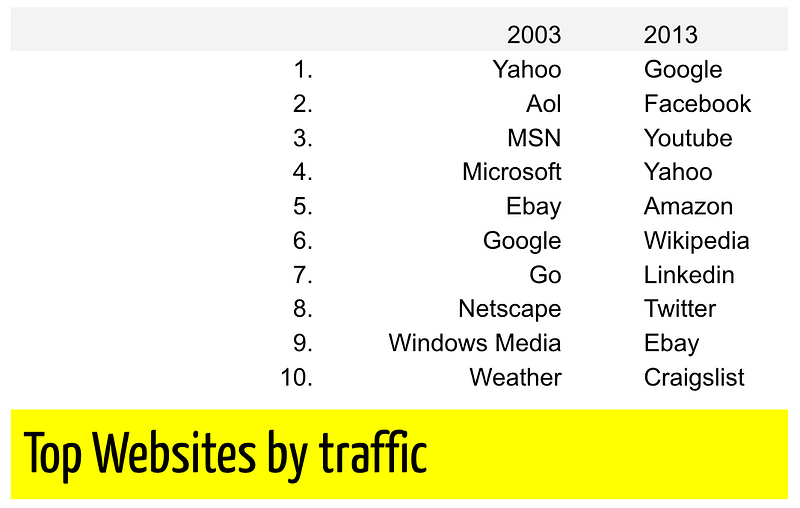

Look at this comparison. In 2003, the top websites — Yahoo, AOL, MSN — these are all just content publishers, publishers. In 2013, they’re all platforms. Google with Gmail, with Maps, with all the apps that they have, Facebook, social networking, YouTube you can upload things. Yahoo now has more of a user generated aspect. Amazon, with its marketplace that Steve was talking to you about a second ago. Think about that shift. All of the top 10 sites in the US right now have a platform element to them. All of them have an user-generated aspect. In 2003, almost none of them did.

This is the change that happened. This is the profound shift that happened in the web. It’s from passive to active. It’s from a passive experience on the web to an active one, and it’s from consumptive, where you’re just consuming information, to participatory, where you’re engaging on the web with it. You’re part of it. The web is what you make of it.

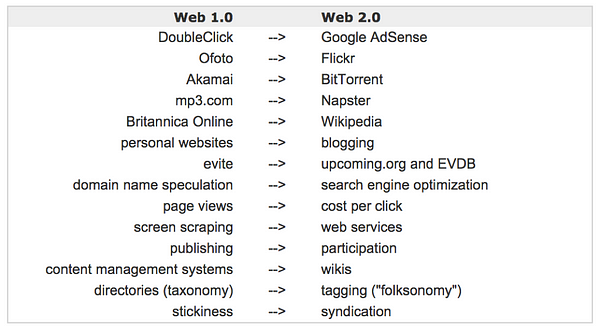

My friend Tim O’Reilly wrote this article called What is Web 2.0? I’m sure you guys have seen Tim talk about at some point; he presented it a lot of conferences here in D.C. He observed this phenomenon and dubbed it, web 2.0. Exemplified by the shift from Ofoto, which was again, just this publishing platform for pictures, to Flickr, where you could upload your own pictures and find other people’s pictures. It’s this profound shift between this 1.0 view to this 2.0.

Architecture of Participation

He wrote something really interesting about this notion of web 2.0. He said, “The key to the web, the change that’s happened is that we have now an architecture of participation.” The web is architected in a way where it’s participatory, where you can engage with it and you can add value. You add value, and you appreciate it, you like uploading your own pictures, uploading your own videos, and you find value in that. Just as importantly, when you do that, you add value to the web itself. Then, the web gets more meaningful for your friends, for your family members, for other people who you don’t even know. That’s the power of the web, that we’ve architected it in a way where you can add value to it, where you can be participatory, and it gets better for everybody.

…for us working in the public sector, this is the question we have to unpack: how do you make an architecture participation work for government?

I think for us, working in the public sector (…I’m just 6 weeks in so I think I can say that, you tell me if I can’t), for us working in the public sector, this is the question we have to unpack: how do you make an architecture of participation work for government? How do you embed an architecture that is fundamentally participatory inside our public institutions? You’ve may have about this before. You probably heard about this idea of Gov 2.0, and government as a platform. What I wanted to do today in this conversation was talk about specifically what those terms really mean — based on examples we’ve seen so far, and some ideas of what we want to do next.

Community as Capacity

The first one really puts open data at its core, and it’s this idea that Chris Vein, the former deputy CTO for the federal government, coined, called “Community as Capacity.” As you all know, and I am learning very quickly, a big challenge in government is getting the resources and the capacity you need to get stuff done. You have a great idea, you want to build a great visualization like the maps and apps you’ve seen. It’s hard to find the resources to do that sometimes. Chris made a good point, however, which is that sometime you can look outside city hall, or outside federal government to get it done. You can look to the community as capacity. This is something that’s at the heart of open data, its promise to unlock the potential in the community for innovation.

A good question is, how do you get value out of open data? You just put this data out there. We’ve opened up 250 data sets in Los Angeles. It’s thousands at the federal level. Ok. So you put this data out there, then what happens? Does anybody build anything on it? More broadly, how do you realize the potential of open data?

I don’t think, “If you build it, they will just come.” No, they just won’t. Indeed I’ve actually studied a lot of cities about how they’ve done an open data program: Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, etc. The cities that have been successful don’t just publish data, cross their fingers, and hope for impact. They get out their, and actively put data to work.

The cities that have been successful don’t just publish data, cross their fingers, and hope for impact. They get out their, and actively put data to work.

By studying them, I’ve distilled these 4 key lessons.

- You’ve got to open your doors. Actually open your doors — that’s not just as a metaphor — you’ve got to let people come inside.

- Create a sense of community where people are actually coming together and knowing each other.

- Back good people with real support, that if people are doing something meaningful with your data, you’ve got to actually give them support and resources to make it better and sustainable.

- Then, you’ve got to make it count, because you’ve got volunteers, you’ve got people who are giving their time, energy, and talent. You’ve got to make that real. You’ve got to make sure that that impact, that technology they build, that insight that they have, has an impact.

The Chicago Story

I’m going to give you probably, I think, the best example of an open data community in the country: Chicago. I’m from Illinois, I’m a little bit biased, but in general I think this is probably the best example. This is a picture of the Chicago OpenGov Hack Hight.

This started as just 4 people coming together to say, “Let’s use this open data coming from the city.” Then, the city’s CTO, John Tolva, would show up, and add a word of encouragement — and maybe a bit of beer and pizza. (Note: Pizza in Chicago is really good.)

These folks decided that, instead of just doing these random events every now and then, let’s just come together every week at 6:00 at a coffee shop, and just work, and spend 2 hours building technology for our city, to help it work better. They started doing that, then other people heard about it and they wanted to join the popup meetup. Soon, they couldn’t fit in the coffee shop anymore. Then, they moved to a local coworking space, 1871. Now, every week, every Tuesday, at 6:30 P.M., dozens of people show up to code on civic data.

Just take a second and think about that. Every week, you have 50, 60, 70, 100 people showing up to use open data to make their city better. That’s a community, and it’s a community that gets stuff done.

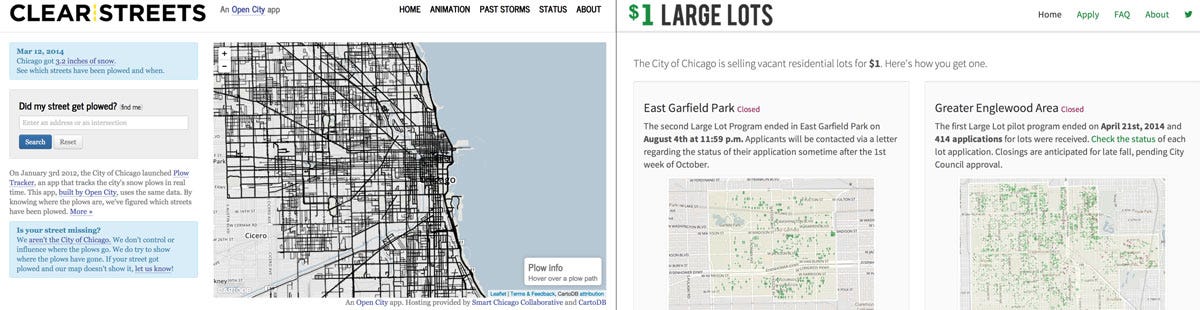

Here’s an example of an application they built, it’s called Clear Streets using open data. In Chicago, as you can imagine, it snows a lot, which I know it does here as well. (It doesn’t snow a lot in L.A., so this isn’t a problem for me.) In Chicago, it snows a lot, and they have street plows going through and clearing out the snow, and people are wondering, are they going to clear my street? Are they going to plow out my street? They took open data about the location of all those streets, of those plows, and lets you track in real time where they are and when they’re going to come to your street. Hugely popular in this city, for a good reason.

Here’s another example. They built LargeLots. The city had this program where, for $1, $1, you could buy a city owned property. No one knew about it. If I knew about it, I’d buy lots of properties in Chicago, but no one knew. They took the data on which properties were available, and then built a simple, beautiful application on top of it. Now, the city has liked this application enough, this is their main portal now for running that program. They took something built in the community, totally outside government, and made it now a government resource.

Those are some examples of how powerful open data can be if you have the right community around it, if you get people engaged. Now, how do you do that?

I think the first thing you got to do is open your doors, not just your data.

San Francisco has done this really well. They have an Entrepreneurship-in- Residence program where they’ll actually let businesses come into city hall for about a month and a half or 2 months and spend time with people, to Scott’s point, just listening. Listening to service line employees and asking, “What are your challenges?” And so learning: do staff really know how to use Excel in the way they need to? Do they have to scan that paper form a dozen times? Do their services really meet the needs of all their constituents? And so forth… What happened? For instance, a team spent time at SFO, and stumbled upon an interesting problem: improving navigation for the blind or hearing impaired. In just a few months, they were able to create a 3D model of the airport. Paired with a bit of navigational software and location aware hardware (read: smartphones), this enables the blind, for instance, to have turn-by-turn directions inside the building. Those are the kinds of innovations you don’t get if you’re not in the thick of it, if you’re not in the midst of the problem.

Philadelphia has a similar program; they have something called FastFWD where they’re actually inviting startups that already have built products to pilot their innovations within government. Yes, procurement’s really hard; we all know that. And yes, working with government is (usually) really hard, too; we all know that. But the team behind FastFWD (New Urban Mechanics) effectively says to entrepreneurs, “Let’s sit down and work on this together. Let us share with you how to navigate this process and let’s work on making it better together.” They’re in their second cohort now. They’ve gotten already 6 startups going through it, and — from what I’ve gathered from both the city and the companies — it’s been really valuable.

After you get people looking at the real problems you have, what do you do next?

I think you have to create a sense of community.

This is a harder challenge than it seems. Some dense cities can say, “Code for Philly,” all together in one place, or host “OpenGov Hack Night” in Chicago at the same co-working space downtown every week. But how do you do that when you’re the Department of Treasury? How do you do that if you’re a state, or even the entire United States of America?

This is something that’s top of mind for me in Los Angeles, because it’s such a big city: it’s 460 square miles, and 4,700 square miles if you consider LA County. (That’s bigger than some states.) It’s a little harder because you can’t have everyone in the same place at the same time.

I think this is where creating a brand and an identity around your data program is really important. OpenTreasury, for instance. Figure out what that brand is, and do the simple things, like say, create a beautiful logo — which by the way is a great opportunity to engage the community — and slap that on everything. Everything: laptops, desks in City Hall, track jackets. Get people to understand that they are part of something bigger than themselves, a community. So even though they may not see everyone all the time, when they see that common identity, they’ll know they are part of the same tribe.

After you create that community, I think you have to back them with real support. That means money.

Money comes in maybe for snacks and sodas, not paychecks and personnel.

We don’t like to talk about money a lot; we talk about volunteer civic hacking. Money comes in maybe for snacks and sodas, not paychecks and personnel. At the end of the day, if you’re going to take something from a one-off volunteer project, and it’s something sustainable, and it’s something meaningful and scalable, you’ve got to support the people who are building it with resources.

These are some examples of institutions that do that.

In Chicago, I think one of the keystone pieces of their open data community is Smart Chicago Collaborative. Funded in part by the Chicago Trust and the MacArthur Foundation, they help transform interesting prototypes into sustainable initiatives through grants, resources, and other kinds of support. In my own backyard, LA, the Goldhirsh Foundation through their LA2050 competition does similar work. And just recently, the GovTech Fund was launched. Serial entrepreneur Ron Bouganim has built a first-of-its-kind $20+ million fund to invest in government technology startups. That kind of commitment from private capital stands as not only a substantial resource, but also a firm validator of the potential in this space.

Finally, I think you have to make it count. You can’t just have people come together, give up their weekend to code atop your data, and then throw it off to the side. These are talented, passionate people who care about their cities. We have to show them respect.

In Colorado, they had a app challenge where the winner of it actually was given a chance at a contract with the state. They created a procurement vehicle that the winner of that hackathon would actually get a contract for the city to buy that software and use it. In Philadelphia, they took a different tact, which isn’t as heavy as providing a procurement vehicle; instead, they just had the mayor show up. Mayor Nutter shared a few minutes of his time to award the winners of the hackathon. Talking to attendees afterwards, I heard in unison a sense of appreciation and surprise: “Wow, my mayor cares about this?” That’s huge. If you think about the appointees, the electeds, that we as government officials interact with, we have access to extraordinary (and free) assets to leverage in support of civic innovation in our jurisdictions.

And even if you don’t, you can get creative. The national education fundraising nonprofit, DonorsChoose hosted a major hackathon, “Hacking Education.” Instead of a cash prize, or even a contract, the winner got something much more interesting: they got to go onstage live on “The Stephen Colbert Show.” This ended up being one of the most heavily attended hack events actually ever, and for good reason. (That photo will surely be hanging very prominently in the winning team’s coworking space.)

As government, we have access to phenomenal resources. If we email someone like Stephen Colbert or a different celebrity and say, “Hey, I’m with the Department of [X], we’re doing something really meaningful, can you help us out?” I bet you 9 times out of 10, you’re going to get an email back that’s pretty positive. We should be comfortable with being creative. Be clever, and reach out and see what happens, because these kinds of things are way more meaningful than a $500 prize.

That’s the big challenge for open data: how do you make it count? And it’s one worth solving. GovLab, which is a research group in New York, has compiled a list of the top 500 startups using open data. I think 500 is just the start. Indeed, McKinsey did a study. They said that the economic value of open data is at $3 trillion. That’s trillion with a T, not B. If we think about the United States being the leader around publishing open data, then we should also strive to be the leader in putting that data to work, to work building businesses, starting nonprofits, improving government, and making a difference in people’s lives. Thus it is incumbent on us as public servants to not only publish data, but also work towards constructing architectures of participation around data.

To summarize those four key principles, I would say this: It’s not just how you open data; it’s how you create friction on top of it. We often want processes to be frictionless, easy, clean. But given that we’re at such an early, nascent, and emergent stage in the open data movement, I would argue that we need to get in the weeds, into the nitty gritty, and explore what’s possible.

The next piece is acting like a platform, thinking about how you, as a government, can be everywhere and anywhere.

Here’s a picture comparing the appointments at St. Peters of Pope Benedict XVI in 2005 and of Pope Francis in 2013:

First, 2005, everyone’s just there, watching. 2013, look. Look at all those devices. That’s just 8 years (and in government time, that’s not a lot).

In just 8 years, we have seen a seismic shift in the way people interact. We are on our phones, everywhere, all the time. This shift is so profound that in fact, the obvious thing to do in response to it is to say, “I’m going to build an app, and I want to put it on all of those screens.”

But here’s the rub: most people don’t use those apps we build.

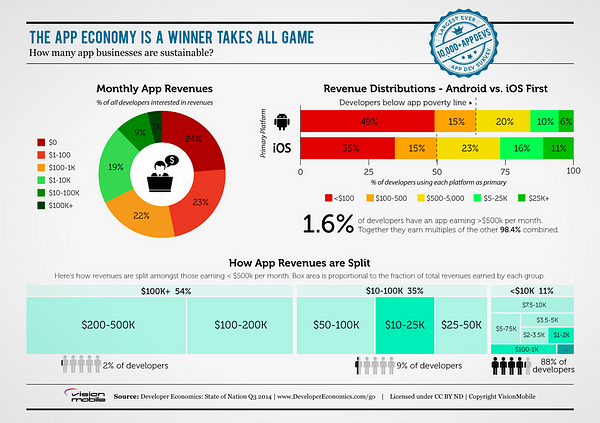

A story along these lines recently ran in TechCrunch, and it said basically, “The app economy is a winner takes all game.” Most people use a couple of apps a lot, and then don’t use any of the other ones.

When we’re thinking about building digital experiences for citizens, we have to keep this front and center. The app economy is a winner takes all game, and I think it’s really hard to compete with Netflix. I think it’s really hard to compete with Facebook. With Google. With Yelp. So let’s not.

Let’s instead partner with them and use those amazingly popular, amazingly beautiful interfaces to deliver our data and our services to citizens directly. Indeed, that’s exactly what we did in the past with Yelp and with Trulia.

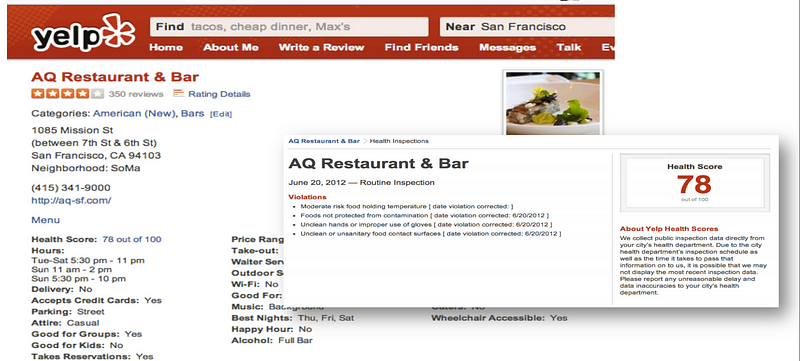

The Atlantic ran an article recently talking about how Yelp might “clean up the restaurant industry.” Curious, because the restaurant industry is their industry, their customers and revenue base. Then, how could and why would Yelp do that? Through and because of data. Code for America worked with cities across the country to open up restaurant inspection scores and publish them in a common format (a data standard). Thanks to this standard, Yelp could integrate this data into their search results at scale — not just one city, but many. That’s exactly what they did:

Now, when you’re in San Francisco, you can actually look for a restaurant on Yelp, you could actually see the health score right there. Just think about that transition for a second. Before, this critically important health score — this data that tells you if you’re likely to leave with a stomach ache —is hidden in the back of the restaurant, tucked away near the kitchen where nobody can see. Now, it’s in the palm of your hand.

Before, this critically important health score … is tucked away near the kitchen where nobody can see. Now, it’s in the palm of your hand.

This shift is possible when you start to partner with these organizations and start to open up your data, and then integrate it with them. We did something similar with Trulia around code enforcement violations. If your apartment, your building owner isn’t keeping up to code, isn’t doing a good job of making sure your building’s safe, you probably want to know that before you move in. CfA got that data opened up, standardized again, and got it onto Trulia. These examples are really just the start. Although these weren’t easy, they did follow a common model, one where scale is key. We had to get multiple cities, multiple jurisdictions onboard. If it were just one, we wouldn’t be able to make that partnership happen. The federal government, then, has an unparalleled opportunity to broker these partnerships. Consider the reach of the agencies you represent. Then ask yourself, “How can we work together to set standards, and get together as a collective force to go to partners like Google, Facebook, Yelp, and then say, ‘Let’s do something with this’.”

I’ll tell you, they’re open to it, more than open to it. They’re excited about doing it because it makes their experience richer for the citizens that they serve. The key here is to consider the citizen experience. You can open up data and put it on your data portal, but does that really go to regular people? Does my mom — that’s the question I ask myself — will my mom be affected by this? Not if it’s just on the data portal. If it’s in Yelp, definitely. The funny story about the Yelp initiative is, my friend at the time, we were going out to dinner, we were picking a place, she was looking at the restaurants in San Francisco to go to, and she said, “Wow, Abhi, have you seen that Yelp has these restaurant inspection scores?” I was like, “Do you not listen when I tell you what I do all day?”

Civic Upsells

A final piece of an architecture of participation is the upsell. That is, how do you get more people doing more with the engagements that you have? How do you get them to be more plugged in?

You give into this every day. Here’s an example.

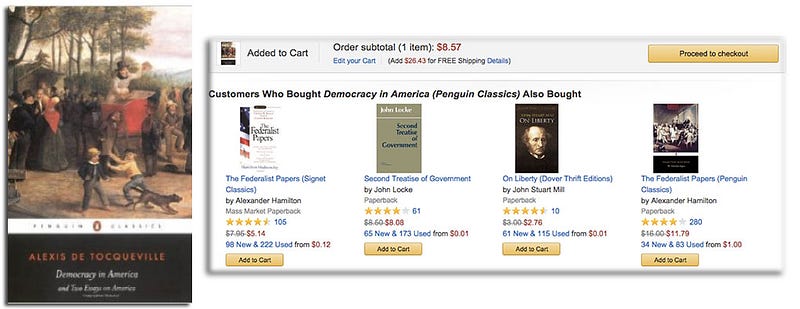

Alexis de Tocqueville is my favorite author. I love Democracy in America. Anybody else here? No? Okay. Thank you. If you go onto Amazon and try to buy this book, right after you buy it, you’re going to see this. Customers also bought, because Amazon wants to upsell you. They want you to buy something else. They don’t want you just to buy one book, they want you to buy two, or three, or even four.

It’s not just Amazon that does that. If you go to a shopping mall or supermarket, you see this:

You’ve shopped in the aisles in the back, and when you’re checking out, you see all of this stuff that you can just quickly grab and add to your cart. That’s an upsell. Grocery stores think deeply — there are books about this — deeply about how to architect those and set those up to make sure the stuff that you’re willing to buy, the stuff that you want to buy, is right there. They think about the upsell. They think about how to get you to do more.

How could we create civic upsells? How could we create those same experiences for citizens using our services from a government?

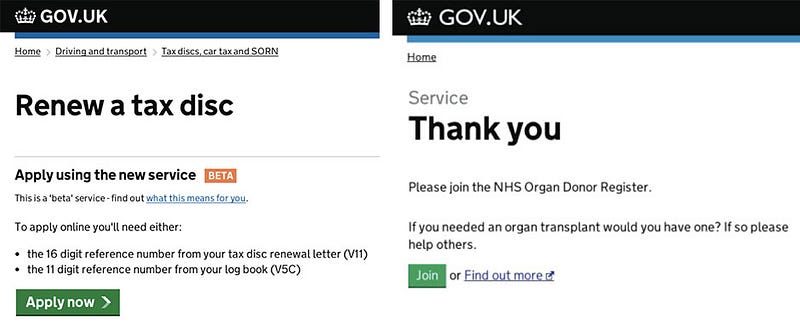

How could we create civic upsells? How could we create those same experiences for citizens using our services from a government? This has happened in the UK. The UK has this great branch called the Government Digital Service, which is helping think through these things and building great websites for the government. They have a bunch of digital services now, where you can go online and pay your taxes, for instance. They call it a tax disc for some reason (because they’re British). After you do that, they typically just showed you a thank you page, but then they added, if you need an organ transplant, if so, please help others.

They added an upsell. What was really interesting about it, they actually tested the hell out of it. They did A/B testing on all the different variations of it, so sometimes they had a picture, sometimes they didn’t, sometimes they had a logo, sometimes they didn’t.

Here’s what’s amazing. One link, that little link they added, added 350,000 more organ donors. Think how powerful that is. They are literally saving lives by just adding a little link.

When you think about the digital services you’re creating, and the digital experiences you’re creating, I would strongly recommend to think about the upsell. Consider how you can get people to do more. You’ve got them engaged, you’ve got their attention. That’s a rare, special thing. Don’t pass up that opportunity. How can you get them to do just one more thing? And with just one more thing, you may end up getting them hooked.

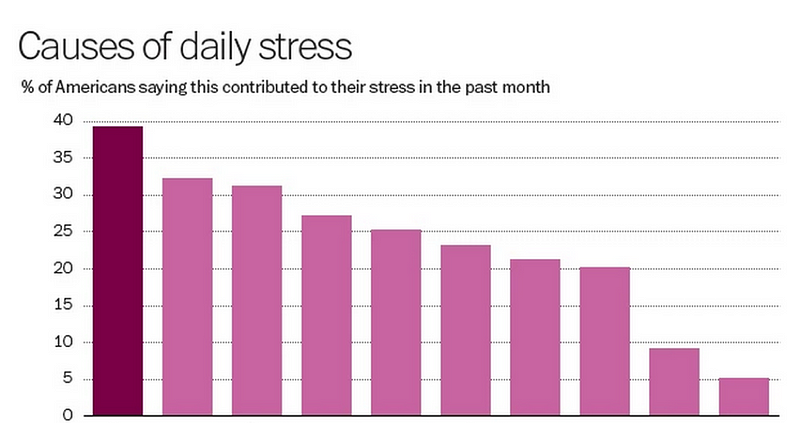

Just in closing, I thought I would mention a recent study done by NPR and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation on the causes of daily stress. What do you think the number one is? Hearing about government and politicians. Honest to God, the number one source of daily stress is hearing about government and politicians:

As government communications professionals, that’s kind of tough. That’s hard to hear. What to do about it?

I think we have to remember that the world has changed. We constructed our communications plans, our strategies in a 2003, 2002 era, where it’s all about push, pushing information out to our constituents. My point here is that it’s about push and pull, read and write; it’s about an architecture of participation.

I’ll end with an old example of an civic architecture of participation, a very old, and very simple one. It comes by way of President Andrew Jackson. In 1835, President Jackson wanted to get people into the White House. He wanted to open up his doors. He was given a big — and I mean big — block of cheese, so he opened up the door and let anybody come into the White House to have a piece. It’s said that 10,000 people showed up to share some cheese with the President. 10,000.

Of course we can’t do that anymore. (Apparently, the smell was more than a little problem.) More relevantly, we live in a different world where you couldn’t fit everyone in the White House, where there isn’t just one door that everyone can walk through. Nor should they. That wouldn’t be fully representative, we wouldn’t be fully engaged.

We have to think now digitally about how to create that kind of engagement.

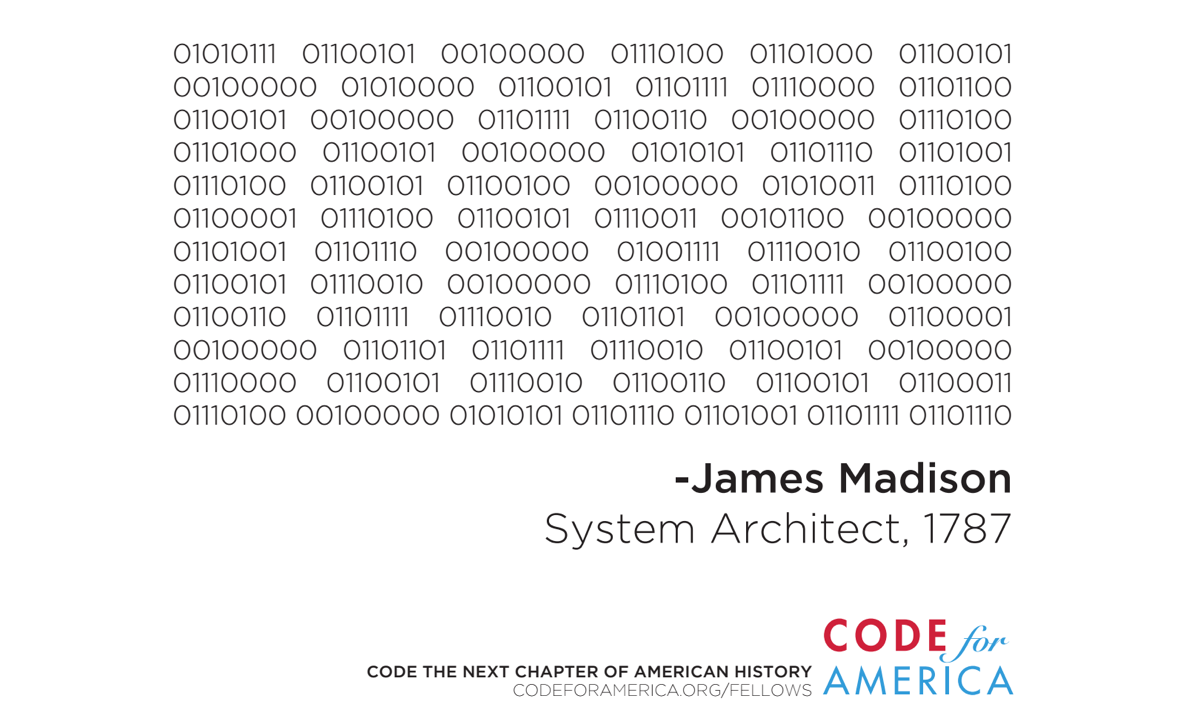

This is the first thing I ever made for Code for America when I started working there 5 years ago:

It’s binary code, and even if you can’t read binary, I bet you can guess what this is: this is the Preamble to the Constitution, changed into ones and zeros. “We the people, in order to form a more perfect union…”

As I do my own work, I keep returning to this image. I keep coming back to it because it’s a reminder that at the end of the day — no matter what technology, code, app, or platform we are building — what we’re really trying to do is something old, something core to who we are.

We the people are forming a more perfect union.

We the people are creating a more perfect government.

We the people in this room, and “We the People” who aren’t but need to be in the process.

Because, at the end of the day, yes, the web is what you make of it, but more importantly, government is what we make of it.

(Many thanks to my former colleagues Tim O’Reilly, Jennifer Pahlka, John Lilly, Scott Burns, and others for their thoughts and inspiration leading to this talk.)

By abhi nemani on December 23, 2015.

Exported from Medium on April 4, 2021.