Last evening, I had the pleasure of having dinner with Remi, the conference organizer, where we started talking about the conference, about data, and about the goals for this conversation. “What are the goals for this conference?,” I asked. He repeatedly mentioned one question: how do we drive value from data. We’re all opening up lots of data, you heard about New York opening 2,000+ data sets, so you’re seeing lots of data get out there, and you’re seeing measures like $3 trillion dollars of value apparently coming out of it.

All of us have to be asking the question: How do we actually take this data that is being opened up and turn it into meaning, turn it into value, turn it into social outcomes that make our cities work better? Today, I’m going to give a little bit of a different presentation than was initially built, based on that conversation — written hurriedly at the hotel last night — so again, apologies that this is a little off the cuff.

Today, I’m going to talk a little bit about how to build a civic technology ecosystem. How do you get the various different actors within a city using data to derive meaning?

You’re going to hear a lot of conversations today, you’ve heard them already, about data science and data analytics, about how you can take data and do really deep and meaningful analysis. We’re doing that in LA, we’re doing some modeling around how to reduce some pedestrian auto collisions, how to reduce worker’s compensation, but what I’m focused on a lot is how we actually build this community. I wanted to share that with you all, if you’re all right with me going a little bit off the cuff. The question you have to ask is how do we put data to work within the community. Before we do that though, I want to see a show of hands. How many people work for the government? Not that many. How many people work for the private sector? Great. How many people work for NGOs and Academics? What you’re seeing here is a really broad spectrum of attendees.

Typically, I go speak at government conferences, where it’s all kinds of bureaucrats like me and we all just talk about how annoying procurement is, but instead here we’ve got this cross-spectrum of people, and so the question is how do each of you, in your various different roles, work together to use open data effectively?

I’ve got four key principles, the first is focusing on the user.

Focus on the User

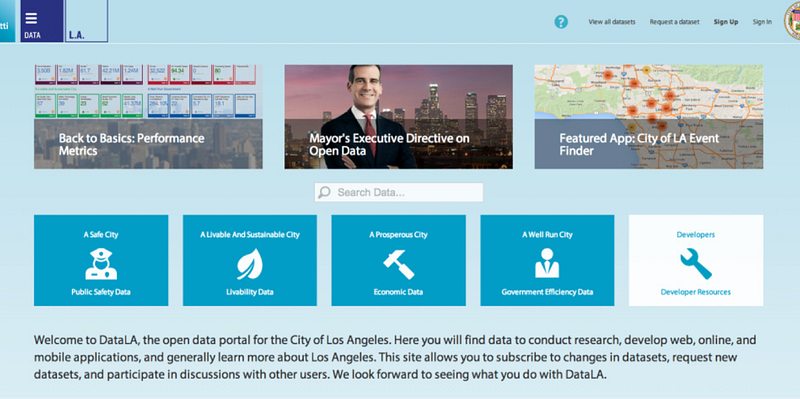

This is a picture of our first data portal from the city of Los Angeles.

This was launched in June 2014, about seven months ago. I started a few months after the launch — in September — and I figured it was a good opportunity to get some feedback and do some user testing. I went around and started doing some basic user feedback. I just knocked on doors and asked people, “Does this site work for you? Are you able to get the data you need from this interface?”

It was interesting, very interesting, in fact, the feedback that I got the most kind of blew my mind. It was, “Abhi, yeah… kind of, but I don’t know what data is.” “What is data?” was the question that I got asked the most. Even someone in my office asked me that question.

“What is data?” was the question that I got asked the most.

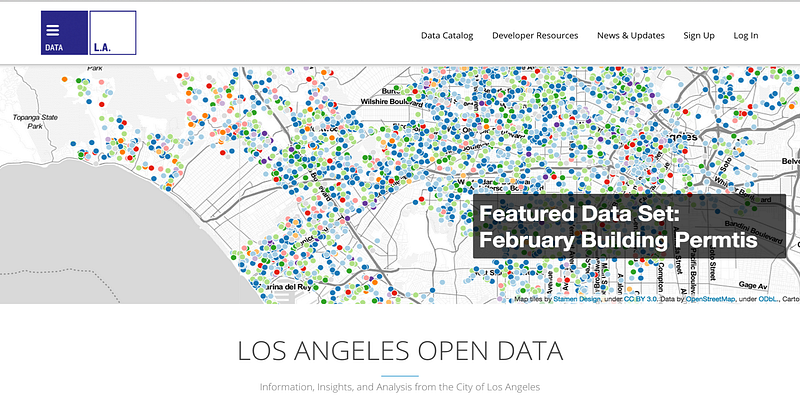

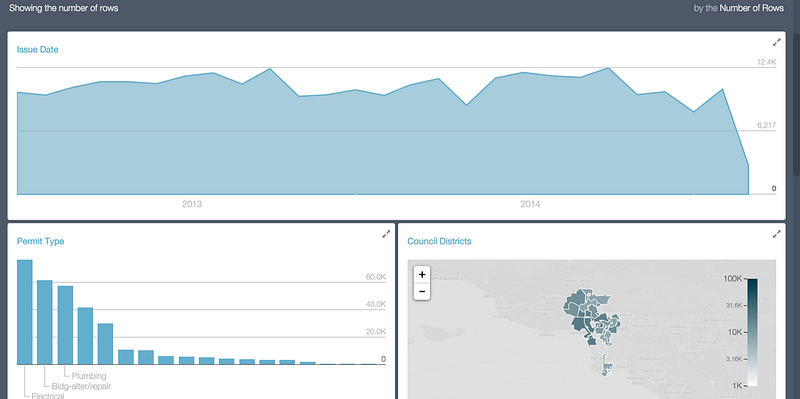

What I decided then is we should think about interaction around open data that visualizes it compellingly, to let people really know what data is and how it affects them. Simply enough, we redesigned the portal a month ago, this is the new look of data.lacity.org and just at the front it’s pretty basic.

We just put a map, we put points on a map that’s kind of beautiful, it’s Easter themed, because we’re coming up to Easter. It shows building permits that you can actually zoom in and find them near you. Scroll down, there’s search functionality, there’s discovery functionality like you see in most data portals, but the key feature was I wanted to say right there front and center, here’s the data that can matter to you.

We keep it relevant too; if there’s a particular event one week, like this last weekend in Los Angeles we had a big bike festival called CicLAvia, where they shut down parts of the street to let people just bike all along the street, so we put a map of the route front-and center. We made it relevant and visual, and here’s what happened when we did that.

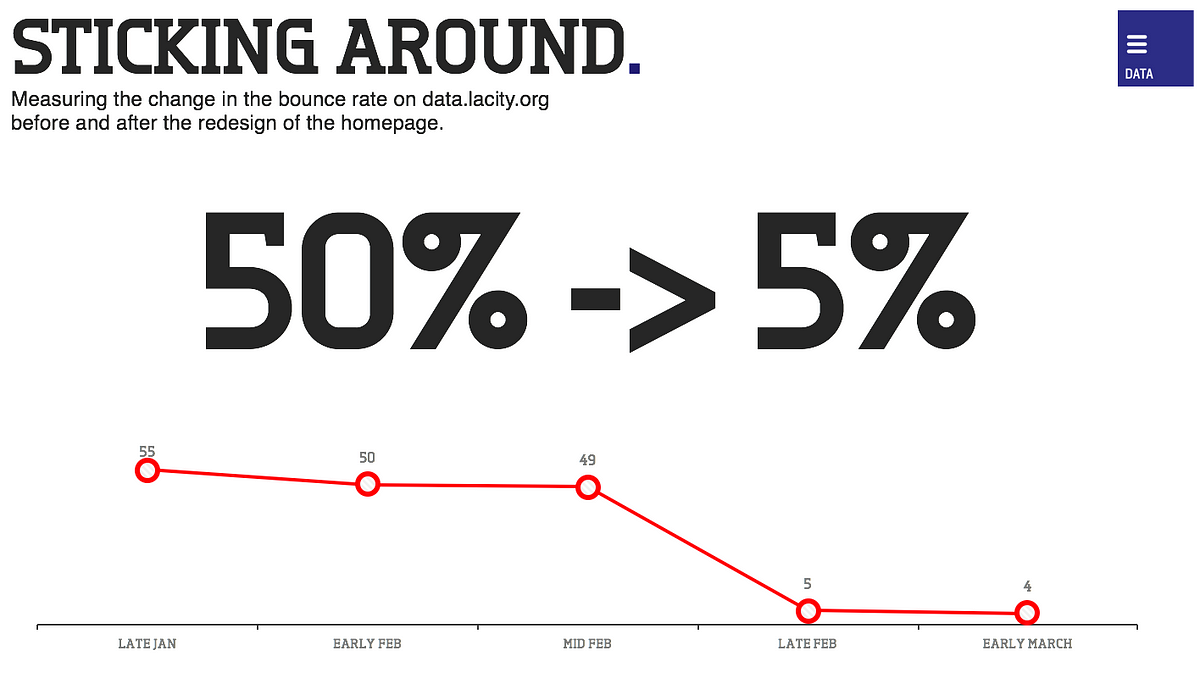

The bounce rate, for anybody who knows technology, this is like if you go to a website and you don’t find what you need and you leave immediately, that’s called bouncing off the site. Our bounce rate before hand was 50%, half the people that came to data.lacity.gov went right away, not great for me. It dropped to 5%. Just by talking to people, figuring out what they wanted, what their problems were with the interface, had this kind of a dramatic shift in less than a month.

Just by talking to people, figuring out what they wanted, what their problems were with the interface, had this kind of a dramatic shift in less than a month.

I bring this up as we think about building open data experiences, if you think about building open data programs, keep in mind the user. Here’s just a preview by the way, of what the new data view site will be… right now it’s just spreadsheets on the internet, which it is. If you just go, it looks like a spreadsheet on the internet. This is what it’s going to look like soon, where every data set is going to be visualized and made interactive for people to explore and understand in a more meaningful way:

That’s the first principle, focus on the user. The next thing I think is, changing the citizen’s experience.

Change the Citizen Experience

We tend to think of open data as something that’s on a portal or maybe on an app that someone’s built, or maybe you download to your computer and do some research on. I think that’s just the start, because the open data that we’re providing can be really meaningful to private businesses, and the interactions you all are creating every day for citizens. There’s no reason you can’t put this data to work for your company. Here’s an example of that. The Atlantic wrote this article, How Yelp might help clean up the restaurant inspection industry. In the states, we have these things, these are restaurant inspection scores, do you have these in France? Yeah. Are they usually hidden in the back of the restaurant, where you can’t see them? Yeah.

This is a problem, right, because you want to get this information before you choose to go to the restaurant, let alone when you go into the restroom after you’ve ordered the main course. What we thought of, this is when I was back at Code for America was, can we take this data that typically is hidden, and put it into the palm of your hand?

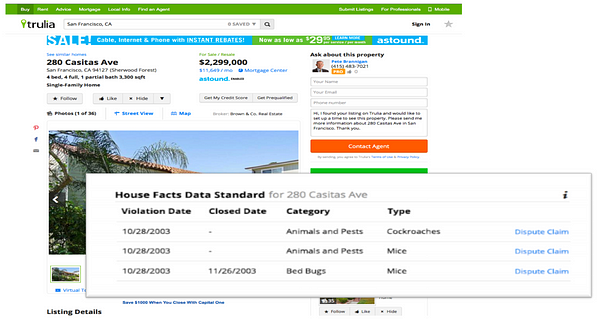

Trulia is a very popular apartment search website, having recently moved to Los Angeles, I can tell you it’s very valuable, even though rents are really high. What they did is they took building inspection data; is your landlord a good landlord? Do they keep the building up to code? Are there termites, are there rats? The city is actually doing a lot of work to inspect that, they send inspectors to apartment buildings to see what’s happening, but again, that data, that information typically lives in some code enforcement, frankly piece of paper. If you’re lucky, excel page, if you’re really lucky, web page, but no one is lucky enough to actually have a citizen go to that web page and check it out before they pick an apartment.

I’m sure none of you have ever done that before picking a place to live. Now, any time you’re looking for a place in a place that has this open data, you get that right in front of you. For the private sector folks in the room, I would encourage you to think about this: Think about the work that you’re doing, and how you might be able to integrate open data into it, to improve your business operations, but also to improve the experience of the customers that you have. The broader point here is, instead of thinking about building more civic applications, which is what we tend to think about, how do we make all apps a bit more civic?

The third piece here is enabling community.

Enabling a Community

Brett talked a little bit about what keeps him up at night, this is what wakes me up in the morning. The idea of building a really thriving, engaged, civic technology community within my city, within Los Angeles. What I did when I came to LA is I took some time to study what worked in other cities. In my past role at Code for America, we spent a lot of time working with other cities to set up their open government, open data organizations. We worked with cities like Chicago, like New York, and like Boston, to actually develop their open data communities. I took some time, I sat down and said, “All right, what do we do, what worked, what didn’t work, and what might be a model for us to apply here in Los Angeles?”

The first thing you have to do is you have to create a place where people can work on good problems — where good people can work on good problems. This sounds simple, just like having a place where people can come together, but it’s very powerful, because what right now, what typically happens with open data is somebody will go into their basement with their computer, go to a web site and pull it down and work on it themselves. Maybe they’ll go to a coffee shop and meet with a couple of their friends and work on it together, but never do those communities get stitched together, unless you find a way for them to come together.

Second is building an identity. People like being part of a group, people like having their tribe. You need to create that sense of identity, and it’s code for Boston, there’s Beta NYC, it’s frankly as easy as creating a brand, but once you do that, you can start putting stickers in the back of laptops, as you might see for some people over here, you can start having common message boards and threads, you can just create a sense of all of these people are part of a common group, and that creates group cohesion. It’s not just random people meeting up randomly, you’re a part of this group.

Make a Challenge

Then, you’ve got a challenge of them to get something done, and here I’m talking to mostly the folks who work inside government. It’s us who see the really hard problems from the other side of the counter. It’s us who see the challenges that need fixing, that too often don’t get fixed, so we need to create mechanisms where we can give those ideas, give those opportunities to citizens who are interested in using our data, and say, “Love that you’re interested in our data, love that you’re interested in making our city better, here’s something you can do, here’s a hill that you can take.”

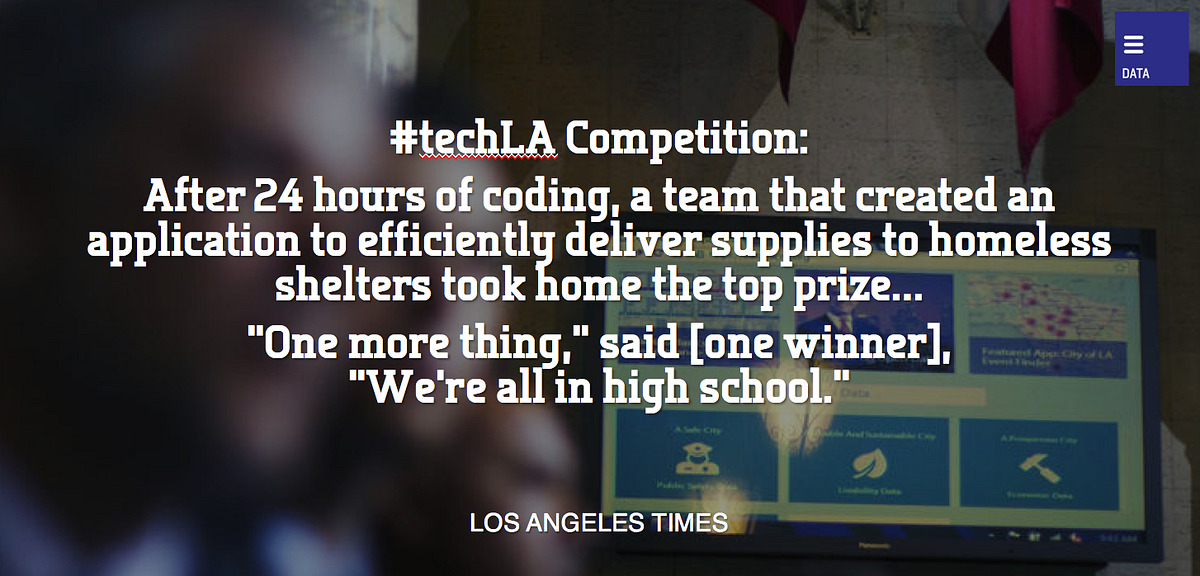

In Los Angeles last year, we did something like this, we had a #techLA competition. It was a 24 hour hackathon, and they built an app that made it easier to find homeless shelters, which I know this is something you’re passionate about, and the great thing is the winners of one more thing were all in high school.

It’s really people of all ages who are able to use this data to solve problems. This year, instead of just doing the one hackathon, as I was mentioning, because we want to make it a more of a community building effort, we’re doing a broader year long what we’re calling X Prize for LA, where we’re actually challenging people around key issue areas, for instance water conservation, which is a central challenge for us in Los Angeles, also immigration reform. Taking these big issues that we have and saying, “Hey citizens, you’re interested in working with us? Here are the things that we want you to do, and if you do it, we’re going to help you out. We’re going to give you resources, we might give you a city contract, we might get you a Hollywood star to do an ad for you, because we’re in Los Angeles and we can do that.”

We’re thinking creatively about the way that we can motivate people to take on these challenges. Finally, I want to talk about the fourth piece, which is institutions.

Work with, not against Institutions

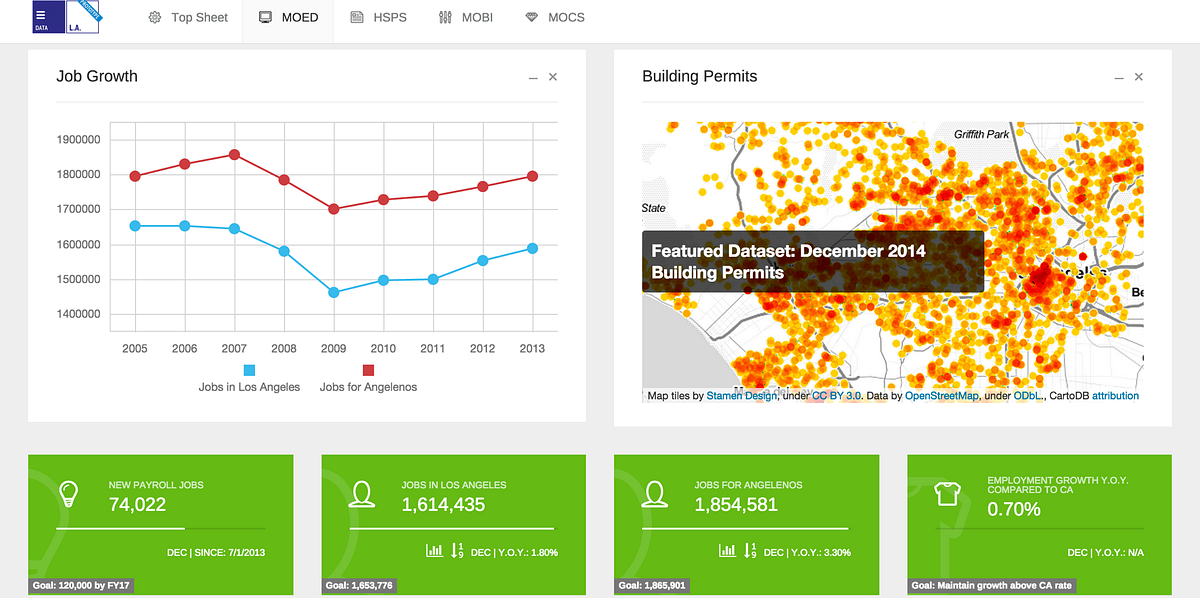

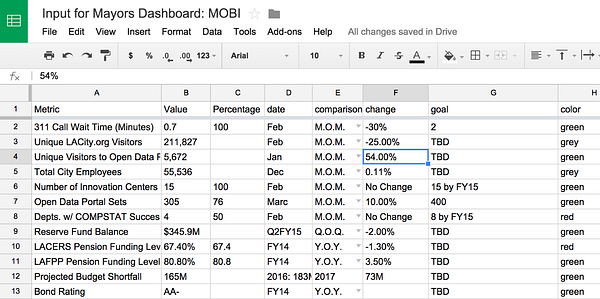

One thing we talked about last night was this question of sustainability. You might build something interesting while you have it, chief data officer in office, but what happens if that guy leaves, or that woman leaves? What happens if that major turns over? This is where I think institution building is really important. You’ve got to build a culture within City Hall, and then you also have to build capacity outside of City Hall. Here’s one way we’re trying to build culture within City Hall. We’ve been working in this program in performance management, and the mayor one day said, “Hey Abhi, can we build a dashboard that I can track all of this stuff on?” He actually asked me that on a January 2nd, and wanted it done by a January 6th. Sometimes things move fast in government.

We built this dashboard for the city. The reason I bring this up is for two reasons. One, the way we built it was on Google docs. A lot of times, people within the government don’t have as much technical familiarity, they can’t go in and edit code on GitHub for instance, but they can at a Google doc or spreadsheet.

The second reason I bring it up is, after we built this for the major and we sent it around the city, I can’t tell you the number of departments that reached out to me and said, “Hey, we want a dashboard just like that.” That’s called momentum, and that momentum can lead to culture change. That’s what we’re trying to do within the city, so even if major’s office staff turns over in 4 years, hopefully 8, there’ll still be that capacity within the organizations themselves, within the departments themselves, around technology.

That’s only part of it, and I keep talking about Chicago, which I kind of hate, because Brett’s loving this. Chicago has this great organization called Smart Chicago Collaborative. It’s a collaboration between the city, between the Chicago trust and the MacArthur Foundation. It’s a non-profit specifically focused on using technology for good. What I love about what they do is they’re committed to taking the innovations out of hackathons or out of hack nights and turning them from one off projects into sustainable solutions. They do things like make grants to teams that build interesting things, they take fellows from these groups and say, “Hey, come spend a year working with us on this problem,” and they provide things like free hosting, that make it easier, that lower the barrier to entry for sustainable solutions.

I love this model, and when I went to LA, I told myself, we need to recreate this in Los Angeles. I’m pleased to tell you that we actually have, we built an organization called Compiler.LA, which is our version of Smart Chicago. What they’re doing is building civic technology, so they’re working with non-profits, with the governments, and helping them solve solutions directly. More importantly, they’ve committed 10% of all revenue generated from any contracts they have to community building. This means we’re going to have an actual source of ongoing revenue to fund innovation throughout the city that doesn’t come from the city government. Back to that point about sustainability, this creates a capacity within the community that’s there long term.

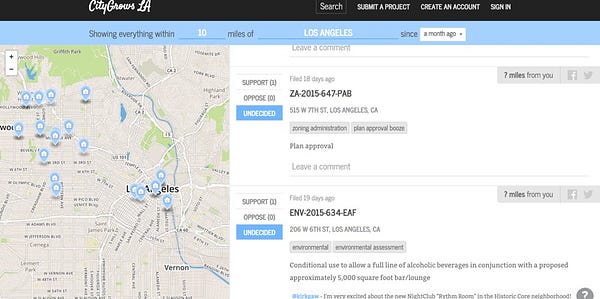

This is an example of something that they built, it’s called CityGrows.LA, and what they do is they track all permits within the city, they scrape it from our website and let people comment on whether they like it or not. It’s own kind of crowd source planning effort. The last thing I’ll just say about the community side is it’s great to have individual organizations like Smart Chicago, like Compiler.LA doing this work, but to really grow and sustain the broader civic technology movement, we need serious capital, and I think someone back there said the word venture capital, so we should talk after this. What we need are real investments to take an organization that’s built a prototype and help them become a startup. That’s what venture capital helps do.

The one I just want to call, there’s a couple of great foundations that do this work. There’s one in LA called Goldhirsh, but I want to call out the GovTech fund, because this came out of our work at Code for America. At Code for America, we built this accelerator to help take what we call Civic Startups, which are government focused for-profit technology companies, and help them scale. It worked remarkably well. The companies that we worked with, one of them went from 100 clients to 650 over the last 2 years. Based on the success of that, my friend Ron Bouganim, who helped launch the accelerator, has actually built a venture capital fund focused on civic startups or GovTech startups, that’s a $20 million dollar fund.

It’s plain: governments, foundations, and institutional capital are stepping up to help prop up the civic tech ecosystem.

Just in closing, I want to make two points, we think of technology as something where we’re trying to get rid of friction. You want your application to be very smooth. You want it to be quick, you can go from getting a user to making a transaction. I think with open data we have to take the exact opposite approach. I think we have to create friction. We have to have those meetups where people come in person and talk to each other. We have to have those challenges where people get together and figure out what they want to do, because it’s with that friction that you figure out what’s possible, you have the conversation and get creative.

A topic that’s come up today, to open up data we need to know the value of it before we do. I so strongly disagree with that. I think open data has an emergent quality. We don’t know the value that it’s going to provide yet, that’s the beauty of it. We’re creating raw materials that people are going to build great new things off of. We shouldn’t, ourselves as people wearing suits and in government, say that we know best. So often with technology we see that it’s the random person who we never thought of, who can take that data, take that idea and make it amazing.

So often with technology we see that it’s the random person who we never thought of, who can take that data, take that idea and make it amazing.

Last thing I’ll say is, I couldn’t come to France and not make an Alexis de Tocqueville quote, because he’s my favorite author and I just have to do that. This is from Democracy in America:

“As soon as I found one another out, they combine. From that moment, they are no longer isolated men, but a power seen from afar whose actions serve for an example and whose language is listened to.”

This is Tocqueville saying the power of community. This is Tocqueville saying how valuable it is in America, but I think also here in France, for when people come together, what’s possible. Just us here today coming together today is powerful, this is now a community.

My challenge to you is to think about how we can create a broader community within Paris, within France, and around the world around open data, to really make is a light seen from afar. Thank you.