It’s simple. It’s not that complicated, and for any of you who know me, you’ve probably heard me describe it at least a dozen times. (Sorry.)

Basically, I want just a little bit of plumbing, something like a little Lego brick to connect two other pieces together.

All I want for Christmas is to be able to feed an API into a data portal without having to write a line of code.

Yes, I’m a man of simple tastes.

Seems simple enough, but I can assure you, in my time it’s taken way too much effort, and I’ve heard way too many excuses why this isn’t possible. But truthfully it’s the same kind of plumbing If This Then That (ifttt.com) offers for a myriad of different services, services as as simple as email to as complicated as my new best friend from Amazon, Alexa.

I have a strong belief that such a tool could dramatically lower the barrier to publishing good, clean, and useful open data.

Before we get there, let me give you a little bit of an example of how simple something like this should be based on an entirely different, but apt use case with Google docs, the Twitter API, and a simple mapping widget.

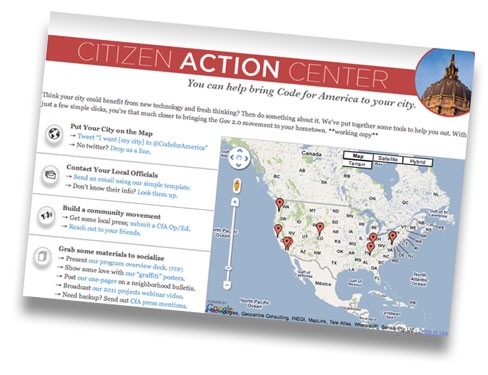

A few years ago on Code for America, we were running a small marketing campaign — bring CfA to your city — and I wanted to add a viral, visual element: a live map of people advocating on our behalf. We made a simple hashtag, #CfA2012 I think it was that year, and said, “Tweet that, and we’ll put your city on the map.” Quite literally (I hoped).

Being the poor man’s hacker that I was I couldn’t rely on tradition JavaScript-based mapping scripts at that time, and candidly I had little experience working with APIs then. I repeat, poor man’s hacker. So I needed a hack, and I thought, “There’s got to be an easier way to do this, where I don’t have to write any real code.”

Fortunately enough there was. I found and easy way to pull in an API feed from Twitter right into Google docs. It’s a simple getData call where all I had to do was copy and paste the feed URL, and Google Sheets did the rest. It grabbed and cached the tweets in a recurring basis in a simple worksheet. (I think it worked about every few minutes — fast enough for our meager efforts.) The platform was easy enough that I could share it with anyone in the office for screening and clever enough to dynamically geocode the tweets onto an interactive map.

undefined

undefined

In about thirty minutes I was able to go from a twitter feed to an interactive map which I could embed on a Wordpress page.

All this was powered of course by the Twitter API and Google Sheets, but for me the user, all I had to worry about was getting the key info I needed (location and content) stored in a canonical place and visualized simply and cleanly. What I didn’t have to worry about was writing ETLs, hosting them myself and keeping them updated.

That I think is what most open data managers, particularly in smaller cities, want to worry — and not worry about — about as well.

So I return to my Christmas wish: let’s do the same thing for open data.

Made plain, this would be a simple web-app where you could input your API URL, login to your data portal, select a refresh rate and the relevant fields, and the press play.

Why?

At the end of the day, that’s the goal of an open data portal, a canonical archive of the data coming from a civic interaction, a piece of technology that people can use in the future to see what happened in the past.

And as more and more civic tools emerge, ideally SaaS, defaulted to open and hosted in the cloud, it should be trivial to store the data from those systems in the data portals we hold up as our open data central hubs.

The elegance of this model, I think, is beyond just making life easier for data portal managers like my (past) self. It’s really that it sets up a dynamic that’s better for both the open data portal visitors, and what I would describe as the open data power users: hackers. The hackers and developers should want to build tools on top of original application, not the archived store. Why? Say I wanted to properly code that Twitter mashup I mentioned before, I wouldn’t want to go and use the data from my spreadsheet, learn the Google API in addition to the Twitter one, and limit my access to whatever caching the “third party” (eg Google Sheets) had set up. I would want to go to the source. (In this case, recall, I am not a poor man’s hacker.) I would want more complete documentation, up-to-the-minute downtime information, and access to developer evangelists and support staff that deeply understood the product.

On the other hand, the open data portal visitors, who in my experience tend to be more academics, researches, and journalists, would have access to the historical data, the longitudinal data that they could look at for analysis on shifts, spikes, or trends over time. And maybe even some simple visualization tools to easily make that map without a line of code.

This is the natural duality of open data usage, which I argue we should mirror in open data publication. And we should bias towards simplicity and scale. Many more cities and so many more open data managers will fall into the non-technical camp, and hopefully many more tools and APIs will emerge within the ecosystem. Let’s make it easy for them to work together. As easy as setting up an IFTTT recipe. As easy as connecting some Lego blocks.

Because as we all know the hard work is using them to build something beautiful.

(That’s what I’ll ask for next year.)