I grew up in rural Southern Illinois. Centralia the town is called. Population 13,000. It’s taken on many lives through its history; beginning first as a railway hub, then a well of natural resource, and later as a small, yet productive manufacturing base for the region. When I was growing up, a nearby highway was built that put town miles off the main interstate, and soon the factories began to close. Growth stalled, and population waned. Today, the town remains a primarily service-based economy, and for recreation, entertainment, or growth, you have to look more at St. Louis, MO, the area’s largest metro — and that’s where my family now spends nearly every weekend. We look to the bigger city nearby.

I mention that because it’s a fact that I’ve tried to keep in mind throughout my work with local government, and in particular with cities trying new approaches with technology. The bigger cities generate energy and excitement, and for good reason: New York City has been groundbreaking in their use of data, Chicago has masterfully bridged the gap between City Hall and the local developer community, and Boston and Philadelphia have established cultures of innovation that you can feel. Examples abound. Our cities are making us proud with what they are making. But what about the small towns and regions? How do we make sure they aren’t left behind? Because even though we can drive off to St. Louis every weekend, there’s still a city here, where thousand of people live and work, and many, many more just like it.

As I look back, now, at the civic technology ecosystem that has emerged over the past 5+ years, I find myself thinking about this a lot. Maybe it’s because I’m spending time here in Centralia, and wishing they had all the great tools we worked on across the country. Maybe too because there continues to be news about more and more cities eager to join the ranks of digital cities, but still feel insufficient answering the most basic question: “Ok, so what do we do?”

What’s the right model for local government civic innovation?

Just as important as any technology is the infrastructure in place to sustain it: human, financial, and technical. When approaching this question — “what do we do?” —we need to have clarity on the systems and structures a city needs to have in place (in-house or not) for sustainable, meaningful innovation. Fortunately, over the past few years, we have seen a number of models emerge for governments keen on leveraging modern technology and modern approaches.

The British Model: Government Digital Service (GDS)

A few years back, in the wake of a colossal Healthcare.gov fiasco of their own, the British government created a technology unit charged with avoiding the next one. The Government Digital Service (GDS) was born, and quickly they began doing much more than just putting out fires. Today, GDS houses 500+ technologists, and has built a brand that it’s been called the “best startup in Europe you can’t invest in,” beating out Silicon Roundabout companies for talent. And for good reason. GDS’s work on Gov.uk, the government’s centralized digital interface merits applause not only for its lovely, user-centric design, but also for their remarkable ability to bring both central agencies and local governments into the fold. (In fact, Mike Bracken, the Director of GDS, received a standing ovation at CfA’s last Summit.) As a model for innovation within central government, GDS is the standard-bearer.

Our cities are more independent and muscular, number in the tens of thousands, and hold responsibility for core service delivery.

Stateside, though, the challenge is more complex, particularly for cities. We don’t have the same manner of government as our transatlantic friends. Our cities are more independent and muscular, number in the tens of thousands, and hold responsibility for core service delivery. Then there are our harsh fiscal realities: small towns, particularly ones with shrinking economic bases, struggle just to maintain current services levels, while citizen demands increase, let alone build out modern technology teams. How could Centralia build its own GDS? And the next city? And the city after that? More broadly, however, an American system where each city was staffing its own distinct product teams seems rare at best, duplicative at worst. Part of the magic of modern technology is that it can scale fast; let’s not ask our cities to recreate the wheel.

Creating a Space for Experimentation: Chief [X] Officers

Many cities have been able to establish high-level technology leadership: Chief Technology Officers, Chief Innovation Officers, and Offices of New Urban Mechanics. These models not only support the smart use of technology, but also tend to drive a broader culture within City Hall around innovation. These positions, however, often structurally lack some of the resources, in particular the human capital, to invest deeply into product or technology development, a la GDS. Many of the most successful and creative cities have had to lean on a mix of partners (e.g. universities, foundations, or volunteer corps) to create the tech they need. For instance, the City of Philadelphia’s Department of New Urban Mechanics is working on procurement reform through the support of Bloomberg Philanthropies; the city of San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Civic Innovation launched its Entrepreneurship-in-Residence program to turn city’s startup scene loose on civic challenges; and famously (and possibly apocryphally) Chicago’s former CTO engaged a team of volunteers to redeploy some Code for America applications, plying them with pizza and beer. Under budget constraints, you have to beg, borrow, and steal innovation.

Under budget constraints, you have to beg, borrow, and steal innovation.

A Marketplace / Component Strategy

A successful and respected venture capitalist, Mary Meeker each year publishes a fascinating summary of internet trends. This year, she highlighted a strategy many consumer apps are taking: moving from multi-use apps to single-purpose. They are “shattering themselves into pieces.” Facebook split off into Messenger and now Slingshot; Foursquare now has Swarm; and Google throughout has taken a multi-app strategy. This uncoupling creates a streamlined user experience for a specific purpose, while taking advantage of common logins, etc, to make on-boarding easy.

When you consider the number of players in the civic technology space—a number that’s growing every day — it’s not hard to imagine a similar single-purpose strategy where cities order off the menu as it were for civic tech they need. Indeed this is starting to happen.

a strategy many consumer apps are taking:

moving from multi-use apps to single-purpose

Facebook could splinter itself into a dozen little pieces, because it had the identify infrastructure (your login) to make it work, and the product strategy to make it make sense. Built at hack-a-thons, contests, and fellowships, civic apps continue to proliferate, but these tools lack that kind of connective tissue. What’s interesting now is that there are efforts to piece them together into a greater whole.

Most notably, there’s Poplus, a newly launched federation of international app makers to standardize on core, common tools and promote their reuse. You could consider it as an effort to standardize around a civic toolkit, tools that those charged with building a civic interface can leverage, saving time and creating some shared infrastructure around the world. Their platforms make it easy for, say, a local good government nonprofit to deploy a government bill and meeting tracking platform (SayIt), and to do so in a way that could link into their other components as needed. They only have a few components now, but their plans are to bring together an international network for tool-makers to build out a robust offering.

While Poplus is focusing on building open source tools, there’s also a concurrent and complimentary movement to build a new breed of for-profit government-focused startups. There’s been explosive growth in this market, as seen in the numbers of startups applying for the Code for America Accelerator, and by the traction they are finding within government and in traditional venture capital. Some have hundreds of local government clients (if not thousands), and have raised substantial capital. Following the disruption eating up traditional enterprise software and other “civic/social” spaces (e.g. healthcare), these companies are offering lower cost software-as-a-service to replace the massive custom builds governments are used to. The result? Dramatically lower costs, better interfaces. And these apps keep getting better. That to me is one of the principle advantage of SaaS for government: there’s a team constantly working to make their solution better and in so doing, helping all of their cities work better.

The confluence of these two trends — the development of reusable open components and the emergence of civic startups—presents a compelling opportunity for cities thinking about changing their approach to technology. With low costs and simplified deployment mechanisms, cities of all sizes could consider leveraging these assets, and indeed many are.

The confluence of these two trends — the development of reusable open components and the emergence of civic startups—presents a compelling opportunity for cities thinking about changing their approach to technology.

Challenges though remain. For the components/Poplus, it’s deployment. Who can cities turn to to help deploy a component, customize it for their needs, and work with them to get it into the hands of the people who need it? There’s an obvious need for an OpenSaaS company to take those components and support the deployment city-to-city. For the startups, it’s market access and visibility. Government technology is a notoriously closed marketplace: little transparency or competition, and the many of rules of the game (procurement) were designed in an era when we approached purchasing software like purchasing trucks or erecting buildings. It just doesn’t work like that any more. Beyond that, both the components and the startups derive value insomuch as they are known of and make sense to deploy. That’s not a light lift. It requires outreach to cities, an understanding of how the pieces fit together, and the supporting infrastructure to actually deliver on those digital services. It requires an ecosystem. We’re on our way there, but it’s early yet.

Pulling these together

Indeed, it’s way too early yet to signal any approach as the approach for American cities, and I suspect we’ll hear more of a remix than a chorus. Bigger cities may take on a GDS-style approach when they have the budget and talent; others may continue to appoint senior leaders to drive forward their innovation agenda; and certainly the mosaic of reusable civic technology will continue to grow richer. These aren’t zero sum. In fact, they would surely benefit from each other. CIOs should be procuring civic startups, and city tech shops should be building new components. That’s the elegance underlying the components strategy: by looking at various pieces of civic technology as components as a broader architecture, then new civic innovations (wherever they come from) can enhance the greater whole.

The rising tide lifts all boats.

But when you talk about platforms, components, and APIs, it’s easy to lost in the ether; it all feels very nebulous and abstract. (I felt so just writing that last bit.) So I wanted to put some flesh on the bones. What would a city experience look like that relied on various components to deliver great digital service? What emerges when you stitch the civic tech space together?

So let’s try it out.

City Digital Services Prototype

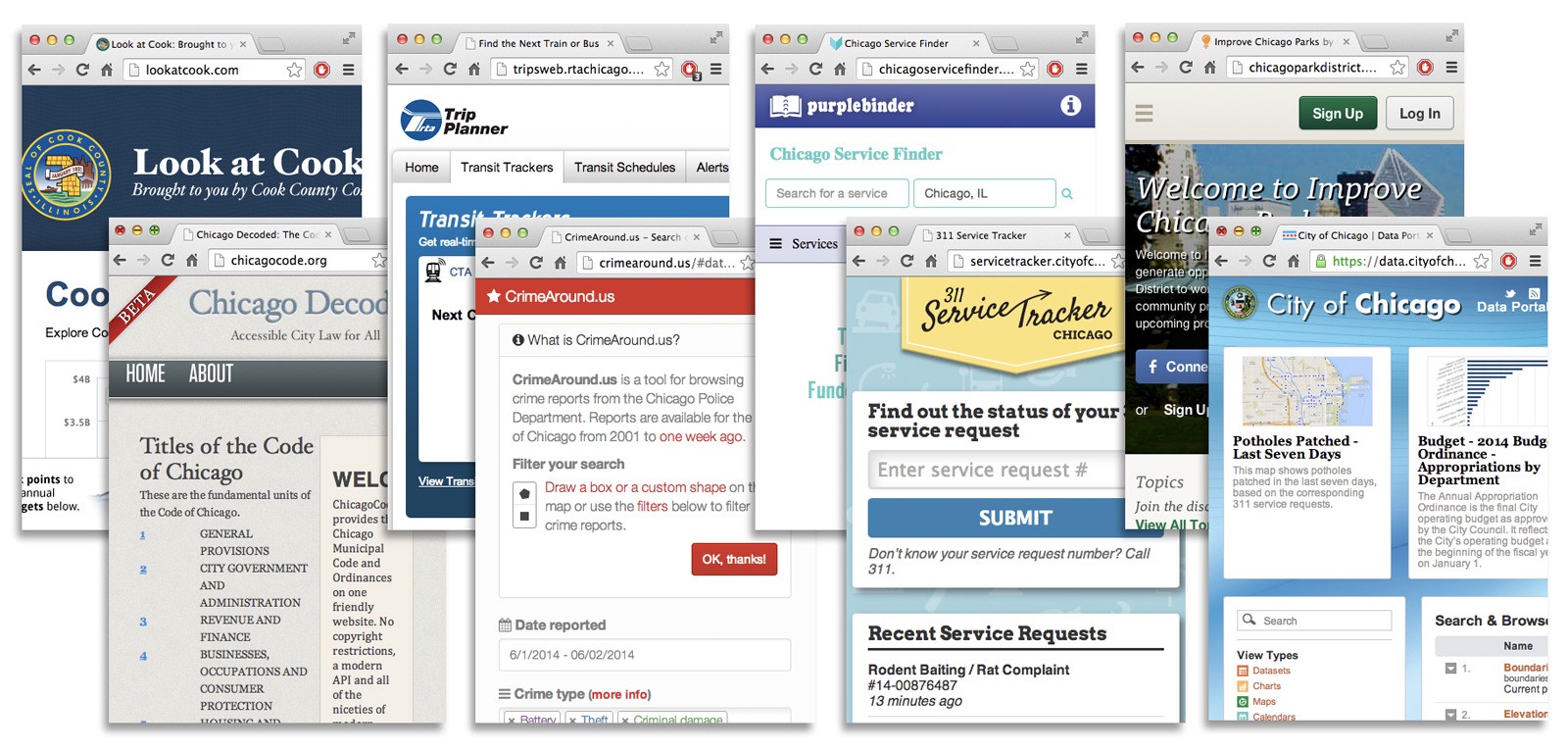

Consider the city of Chicago’s slate of digital services (well, some of them):

These tools come from a host of different sources: some, like PurpleBinder, a social services finder, or the open data catalog, are from civic startups or other traditional IT vendors; others, such as the crime map and Look at Cook, are open source tools built by local groups of developers. You can see here the mix of components that’s possible when you look to the ecosystem. But they are spread across the board—just look at the URLs—making it difficult for citizens to find each service when needed, and more relevantly, without a picture of how these fit together (and ideally instructions on how to replicate it), it’d be tough for another city to follow suit. Where would they start and how?

Put another way, the city has a full digital services stack, but you can’t really see it.

Well, what if you could?

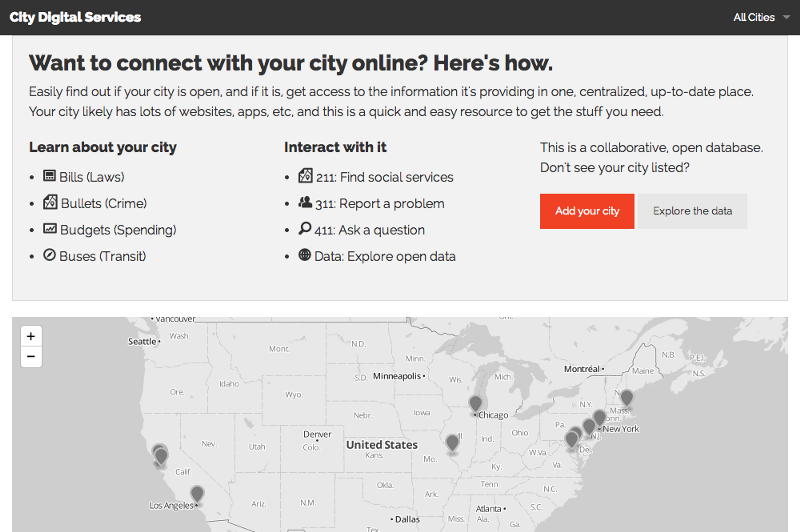

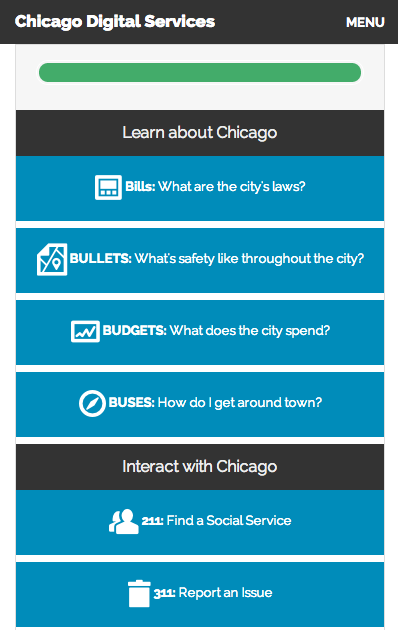

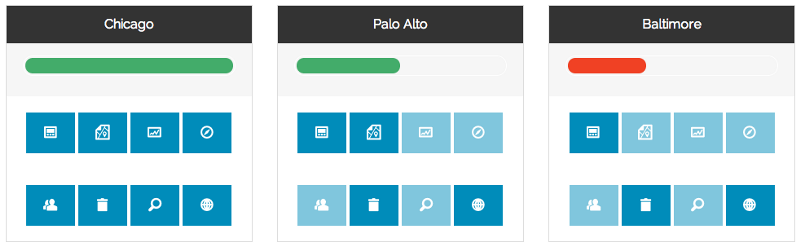

Meet DigitalServicesCenter.com. This is very much a prototype. (And I am very much earning the title, “poor man’s hacker” with the codebase.) It’s a quick attempt to link together various digital services in an area and present them in a streamlined, common, mobile friendly format, city-to-city. The homepage features a list of all the cities, indications of how they are doing, and links to city-specific pages (e.g. Chicago, Oakland, or Palo Alto).

Focus on what matters

My operating principle was to focus on what matters (at least in my view). Instead of a litany of services and links, can we identify the top 3-4 pieces of information and the top 3-4 services cities offer that citizens want?

For the information options, I relied on Mark Headd’s “3 B’s of Open Data” — his recommendation for the three pieces of open data every city should publish: bullets (crime data), budgets (city expenditure), and buses (transit). Since legislative information seems to be an area of growing heat, I appended a fourth: bills. On the services side, the bias was towards simple, common functions (e.g. reporting an issue) where digital tools exist and ideally standards linking them together do as well: 211 (social services), 311 (issue reporting), 411 (inquiries), and then open data writ large for all else (e.g. the city’s open data portal). But there’s no reason this couldn’t be iterative; if over time, we see that a particular component listed isn’t finding traction in our cities, it could be replaced.

Fortunately, each of these areas already have a host of options, both from the open source community and from civic startups, which cities can mix and match:

- Bullets: CrimeAround.Us, Crime in Chicago, Oakland Crimespotting

- Bills: OpenGov’s AmericaDecoded, MySociety’s SayIt, Councilmatic

- Budget: OpenGov.com, OpenSpending, Look at Cook

- Buses: OpenTripPlanner, OneBusAway

- 211: Aunt Bertha, Purple Binder, Ohana, Connect Chicago

- 311: SeeClickFix, PublicStuff, Connected Bits, Service Tracker, Open311Mobile

- 411: CityAnswers, MindMixer, OSQA

- Data: Socrata, NuData, CKAN, OpenDataCatalog, Junar

I’ll add that in an ideal case, the transaction / service options might be more compelling; for example, updating your personal information the city has about you, or dealing with payments or permits. For this prototype I erred on the side of practicality over aspiration: to my knowledge those deeper services are not yet available, at scale, through SaaS providers. So instead of designing what the ideal city digital service center might be, this shows what a real one could be.

(Note: Poplus using a strict definition for their components; for these purposes, I’m using a broader one, defined simply as a single-purpose civic app.)

Keep It Simple

The other guiding principle was to minimize the burden on the city. What’s the least they could do? In this case, city only has to build a scaffolding. It’s just simple HTML, Javascript, and css that bring together the various other sites (e.g. a 311 app) into a simple experience. (Truly simple: at the core, it just a set of links.) Just by adding links to its existing digital services to a spreadsheet, the city is added to the site, and gets a city-specific mobile-optimized Digital Services Center (like this one for Oakland).

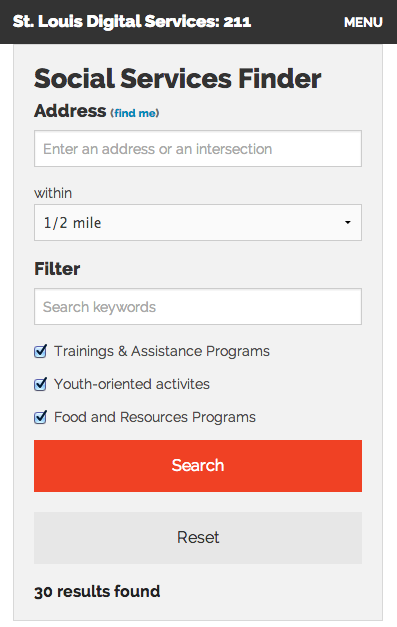

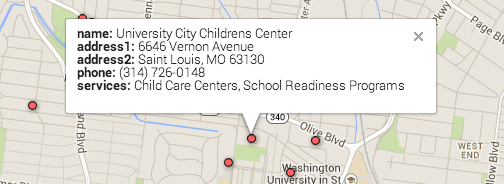

It’s worth pointing out that this site relied on a robust CSS framework called Foundation. Out of the box, it comes with clean styles and importantly a mobile responsive layout, which makes creating new pages or even new apps in the same style rather easy. To test that hypothesis, I created a simple Social Services Finder app, relying on Derek Eder’s template, and the Foundation CSS. It took me under about an hour to get the app up and running with data I scraped on St. Louis’s social services.

You’re sure also to notice that a city’s page doesn’t have what you typically see on a local government homepage. No news feeds or blogs; no description of department; and no educational information about the city’s history or the like. That’s because this is about digital services: the ways you can interact with your city online. As we move towards a digital strategy where content goes where users already are, and while homepages overall are being questioned, the goal here was to centralize the activities you might hope to take online, which you otherwise couldn’t find.

In a certain way, this aligns, I think, with the reason we go to City Hall: to get something done.

City-to-City Comparison

With those two pieces in place—a list of the core digital services and a simple way to present them on a per-city basis—I decided to start comparing city-to-city:

For both cities and citizens, I suspect this may be helpful to see how an individual city stacks up. More interesting, I think, are the opportunities to use a common framework like this to identify gaps and trends in the ecosystem. We can start to see whether, say, 311 is missing in many cities, or conversely that, say, a specific vendor holds much of the market. Consider having quarterly discussions around these core areas: what’s working, what’s not, where are there gaps, and what should we be spreading one city to the next to fill them.

What’s Possible with a Components Approach

Admittedly, this was a very loose way to join the various pieces. Smarter, deeper integrations are needed around data, identify, and design. The point of this prototype, though, was less really to build anything specifically that a city could use — though that’s always fun — but instead to give us all something to look at and consider what’s possible.

Ladders of engagement & the “Civic Upsell”

When you start to see these services put next to each other, you start to think about the connections between them. The notion of an “upsell” is commonplace in retail, online and off. You’ll see it on Amazon after you’ve added something to your cart: consider what other books a customer bought, or think about pairing that new device with a accessory or support package. This same thinking could be applied to the civic space. If we think of cities less as various departments, but one institution with various offerings, then we can create “civic upsells” from one service to another.

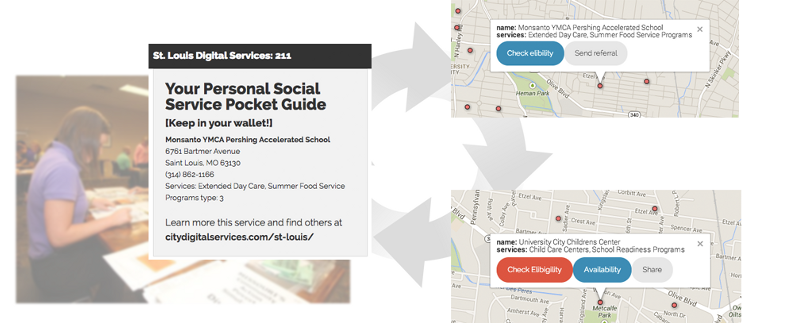

Discovery: Consider the example using the Social Services Finder from above. Often, social service providers in a city have to refer citizens (typically called “clients”) to another provider. If we were to make it easy for those providers to, say, print out referral information, pointing them back to the mobile site, you open up the possibility that they could find another service or opportunity within the city. It thus becomes both a resource for the service provider and the client.

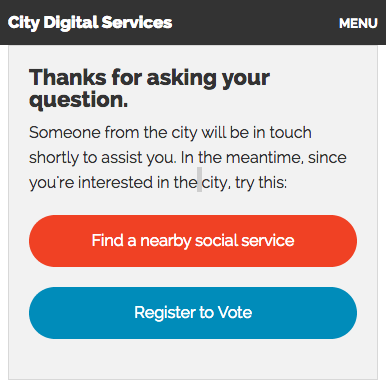

Being more civic: Getting a user’s attention online is always a challenge, and once a city has it, we should take full advantage of it. With the services centralized in one place—and maybe even some, like this St. Louis example—hosted by the city government, you can start to connect the dots between services. After you submit an issue or question, you could be prompted to register to vote or attend a community event; after you submit a 311 request, you could be encouraged to organize your neighbors to address it; or simply enough, after you look up a social service, you could be given public transportation options for getting there.

digital services can be organized to enable a “ladder of engagement”

In this way, digital services can be organized to enable a ladder of engagement— clear and simple pathways to deepen engagement by following one activity with another.

Towards standardized discovery

Government usually has the reverse problem that consumer apps are trying to solve with the single-app strategy: there are already too many websites for a government. In fact, it got so bad the federal government had to put a freeze on new top level domains. Cities have a similar problem, and even now as better, more compelling digital services emerge, there is no common way to find a service city-to-city. Top level domains span the gambit (e.g. Oakland’s url is oaklandnet.com, New Orleans is nola.gov), and even with widely popular services like an open data portal, there’s little consistency. That means if you wanted to compare one city’s data portal to another, or better yet, their data, it’s next to impossible.

If cities were to adopt common infrastructure with these components and tools linking them together, we might inch towards some consistency — at least a hack. Think of citydigitalservices.com/[CITY] as a base url for all cities and then /211, /311, etc. That’s not just making the lives of traveling civic hackers easier, but hopefully opening up the door to more cross-city innovation.

Opportunities for new efforts / civic startups

Seeing the prototype Digital Services Center, you may think that there’s only room for eight startups in this space. (One for each of those little icons.) Or if not, you might at least come to the conclusion that there’s only room for eight in one city. I would argue that this approach if fact opens the door to even more entrepreneurship — and may help even with the pace of adoption.

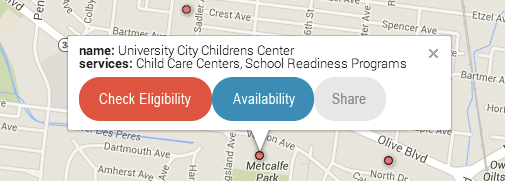

Compare these two screenshots from the Social Services Finder:

The second (just a mockup) features calls-to-action for the citizen that indeed could link to different pieces of technology. The city may use a simple mapping tool to showcase the various options, but then use, say, Benefits Data Trust to check eligibility, Aunt Bertha for availability, and then a new startup specializing in referring clients from one location to another. And this thinking applied to nearly every service. Simply put, each of those buttons is an opportunity for a civic startup. The upshot being that instead of those tools sitting aside the city’s website or another offering, they are positioned together ensuring that citizens can get to the right tool for their needs. As I’ve written before, I do not believe that we could ever build a single app suite to solve all the civic problems for everyone; no, the world is too complex and user needs vary place-by-place, day-by-day. Diversity is a virtue—as is understanding. By putting together the applications in this kind of funnel, government IT managers and purchasing officers can start to see how the pieces fit together, making the sales process for a startup hopefully a little easier.

Simply put, each of those buttons is an opportunity for a civic startup.

I was once told, “Good writing is giving your reader a context within which to think.” Those of us working in the civic technology field talk a lot about this notion, “Government as a platform,” and I wonder if that quote—broadly understood—strikes at the heart of what that means: creating contexts through our public institutions within which others can think, create, tinker, and make. The art of stewardship is doing the least to enable the most. As we move forward with our work recoding our cities, context will become increasingly vital; context for citizens to understand how to be part of the work of government; context for entrepreneurs to identify ways to make that work even better; and context for our cities themselves to deliver digital services we can celebrate.

“Ok, so what do we do?”

There’s a sad irony to this entire endeavor for me. My impulse was to find a way to help my own city, Centralia, but to prototype the notion I again had to look to the bigger cities of St. Louis and Chicago. Fact is that those digital components just don’t exist in my hometown yet, and though I tried for hours trying to deploy open source applications to flesh out a Centralia Digital Services Center, I was left wanting. Either it took too long to deploy the code, or the applications just didn’t apply here. (There is no public transportation system.) I return then to the earlier refrain: it’s early yet.

But let’s keep working. And perfection isn’t a goal. When reading David Weinberger’s Small Pieces Loosely Joined, I was struck by his celebration of the web’s messiness: how it doesn’t always have clean lines; how things have a knack of ending up where they shouldn’t be; how it is perfectly broken. “Links don’t work. Email messages are misspelled,” he rattles off. But he adds, “The imperfection of the Web isn’t a temporary lapse. It’s a design decision… The designers weighed perfection against growth and creativity, and perfection lost. The Web is broken on purpose.” In many ways, we designed our governments as well to be perfectly broken. Decidedly inefficient, competing interests, and complex systems of power. It is those very blemishes that drive us into public service to make the lives of those around us better. Our government, like the web, is what we make of it:

But there is, I believe, something more pulling us on to the Web… The Web is ours… the Web is thoroughly ours in the same way that language is ours. It is of us. It is drenched in that which makes us human: consciousness, sociality, meaning, intention, interest. But now we’re [making things] it in a world that we’re building for ourselves out of the truly human “stuff” of language and passion. — Small Pieces Loosely Joined

N.B. This was meant to be an experiment in creating a digital services center as a way to flesh out my thinking around city tech. If you have any feedback on the prototype, data to add to it, or thoughts in general about the commentary, please do not hesitate to drop me a line: @abhinemani or [email protected]. That’s the only way I’ll get good data on the experiment itself.